|

| Satire of 1791 The Doyen of the Farmers General, borne aloft by his clerks, makes a final journey to oblivion. Musée Carnavalet. Le Doyen des Fermiers Generaux [...] | Paris Musées |

Wednesday, 29 June 2022

The last Farmers-General

Friday, 24 June 2022

Lavoisier and the General Farm

In his career as Farmer-General, the great chemist Lavoisier, exemplified the professionalism and dedication to public service shared by so many of the Farm's senior administrators in the last years of the Ancien régime. Far from regarding his involvement with the Farm as merely a source of income, Lavoisier brought his huge energy and intellect to bear on its problems with every bit as much seriousness and zeal as he showed in his scientific work.

Lavoisier enters the Farm

|

| Portrait of Lavoisier by Jean-Baptiste Greuze Private collection, see Beretta, Imaging a career in science (2001), p.3-4. |

Anecdotal evidence suggests that Lavoisier's scientific colleagues were worried that his new responsibilities would prove too great a distraction, though the geometer Fontaine quipped: "So much the better, the dinners which he gives us will be much improved" (quoted Grimaux, p.32)

Nor were the benefits of being a Farmer-General merely financial; Lavoisier was now marked out for a high-ranking government post - though, in the event, this ambition was never realised:

E. Chevreux, Journal des Savants, November 1859, p.711.

Monday, 20 June 2022

Helvétius, philosopher tax-farmer

|

| Portrait of Helvétius from Ickworth (N.T.) studio copy of the full length portrait by Van Loo exhibited in the salon of 1755. Claude-Adrien Helvétius (1715–1771) | Art UK |

Until relatively recently not much was known about Helvétius's career as a Farmer-General, beyond a few lines in contemporary notices and eulogies. However, in modern times two manuscript reports have come to light from Helvétius's tours of inspection as a Farmer, in the Ardennes and Franche-Comté. The new finds show the seriousness of his commitment to the Farm. According to the editors, Helvétius comes across as a conscientious and able financier, "a commis, serving the interests of his Company"[Desné, 1971] and "an inquiring mind, keen to improve the operation of the Farm, and eager to propose reforms" [Inguenaud, 1986].

Helvétius becomes a Farmer-General

Helvétius came from a distinguished medical family: his father was chief physician to Marie Leckzinska. and was credited with having saving the life of the seven-year old Louis XV in 1717. However, Helvétius's precocious scholastic achievement suggested a different direction: "His father, whose fortune was mediocre...destined him to finance, as an state which could enrich him and leave him the time to make use of his talents (Saint-Lambert, p.6) His father was not mistaken - Helvétius was to become almost obscenely rich; according to Bachaumont, on his death his estate was worth four million livres (Mémoires, 4th October 1772).

The young man was initially sent to work with his maternal uncle, M. d'Armancourt, directeur des fermes in Caen. The historical record from this time preserves only his literary pursuits; he wrote verses, even a tragedy, and, with the support of the Jesuit Yves-Marie André, gained admittance to the Academy in Caen. (Keim, p.15-17)

Tuesday, 14 June 2022

Tax farmers and Philosophers

There are two conditions of person that have greater weight in society than in former times, particularly in fashionable social circles. They are the men of letters and men of fortune....

Not long ago financiers saw men of good birth as their protectors but today they rival them.

Charles Duclos, Considérations sur les mœurs de ce siècle (1751). Chapter X, sur les gens de finance.

The gross and ridiculous financier...no longer exists in Paris. This portrait might have been realistic fifty years ago, when Le Sage wrote his comedy "Turcaret"; today our financiers are very refined and likeable, have fine and agreeable houses and no longer resemble the financiers of old.

Grimm, Correspondance littéraire, 15 June 1753

Fréron, Lettres sur quelques écrits de ce temps (1761)

Alix de Choiseul-Gouffier, vicomtesse de Janzé, Les Financiers d'autrefois (1886), p.24-5

Sunday, 12 June 2022

The Encyclopédie on tobacco

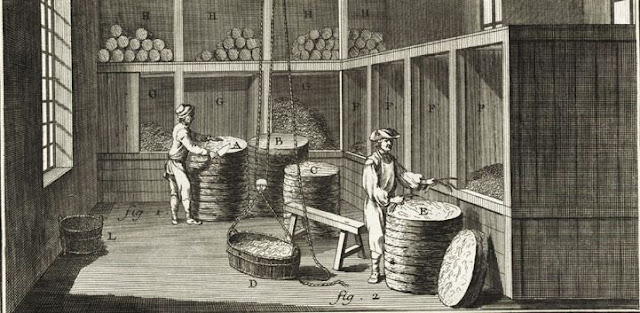

Jaucourt's informant notes that the manufacture of tobacco products demanded neither complicated machinery nor highly skilled workers; however simple operations require care and attention throughout the process, from the choice of materials to the finished product.

The magasins or warehouses for storage of raw tobacco were designed to offer protection from sunlight and humidity. They were very large, since newer leaves had to be constantly moved and piled up to avoid uncontrolled fermentation.

Tobacco was processed into a number of different finished products, each with a particular name and usage. The two most common in Paris were rolls for the pipe and tabacs "en carotte", that is compressed tobacco for grating. The article illustrates the steps in manufacture:

1. L' Époulardage

|

| Two workers sort imported tobacco leaves |

Saturday, 4 June 2022

Tobacco Manufactories

This post is based on a lecture given in 2011 by Paul Smith, a specialist in industrial archaeology with the Direction générale des patrimoines (see references blow).

|

| Manufacture de tabac Architectes: Jacques Martinet et Jacques V. Gabriel, Le Havre 1728. |

Thursday, 2 June 2022

The Tobacco Farm

The Ferme du tabac and the organisation of the Tobacco industry

By the mid century tobacco duties were worth more than 30 million livres a year to the French Crown - some 7% of fixed income - second in value only to the hated gabelle. Like the trade in salt, the tobacco trade was administered as a royal monopoly. In 1730, after a period of control by the Compagnie des Indes, the Ferme du tabac was incorporated into the "General-Farm". It was a huge undertaking. To maintain the tobacco monopoly effectively, every aspect of the importation, processing and sale of tobacco had to be overseen.

This map, which was prepared by Lavoisier in the 1780s, shows the Tobacco Farm's complex and highly regulated pattern of import and distribution. This level of control was made possible by the centralised organisation of the General-Farm with its specialised committees, directors and inspectors. From 1749 onwards the Comité du tabac occupied the magnificent 17th-century Hôtel de Longueville, situated in the centre of Paris between the Louvre and the Tuileries. From here the authority of the Farm extended directly through much of the Kingdom, with "sous-fermes" in the Lyonnais, Dauphiné, Provence, Languedoc, Roussillon and Lorraine.