Here are a few memorable events and personalities from the Revolutionary era in Lyon as depicted in Alphonse Balleydier's Histoire politique et militaire du peuple de Lyon pendant la Révolution française, 1789-1795, 3 vols. 1845-6. I found this particular set on the website of the LYNA Lin Yu-Nu Art Foundation an Art consultancy that operates in Paris, Beijin and Taipei, but the three volumes with their illustrations are also available on Internet Archive.

The Military federation, 30th March 1790

On 30 May 1790 the municipality of Lyon organised a huge civic fête on the plain of Les Brotteaux, involving twenty-eight batallions of the Lyon National Guard and delegates from neighbouring departments. For the occasion Cochet constructed a temple of Concord and a Rocher de la Fédération surmounted by a statue of liberty, the plans for which still exist in the Lyon municipal archives.

Paul Feuga, "À propos de la Révolution et de deux dessins de Claude Cochet", Muncipal archives of Lyons.

http://www.archives-lyon.fr/static/archives/contenu/64parcours/Recherch/feuga/texte.htm

Joseph Chalier, leader of the Lyon Jacobins

The plate illustrates the contradictory character of the excitable Chalier:

He trembled with joy before a model of the guillotine, he fell into ecstasy before a flower, the leaf of a tree, a blade of grass; he wanted to wash his hands in the blood of aristocrats, yet he would kiss the beak of a pet dove, which he called his best friend after his mistress; he declaimed against the absurdities of the Catholic church, but forced his brethren to kiss a stone from debris of the Bastille or a scrap of Mirabeau's clothing. (Balleydier, vol.i , p.32)

The taking of the château de Poleymieux, 26th June 1790

The medieval château of Poleymieux was owned by Aimé Guillin Dumontet, who had retired there in 1785 after an illustrious career in the navy and Compagnie des Indes. His brother had been implicated in the Counterrevolutionary Lyon Plot and the local population suspected that Dumontet himself had assisted in the flight to Varennes. On 26th June 1791 delegates from the municipalities of Poleymieux, Quincieux and Chausselay arrived at the château with 400 National Guard to search for arms. They were later joined by a considerable crowd. Guillin, resisted, firing potshots, the situation escalated and he was finally lynched. It was said that a local butcher dismembered his body; his head was carried to Couzon and his heart to Neuville-sur-Saône where it was eaten in an auberge. The château itself was burned down and never rebuilt. Today only a few stones and the former dovecote(the tour Rysler) remain.

The medieval château of Poleymieux was owned by Aimé Guillin Dumontet, who had retired there in 1785 after an illustrious career in the navy and Compagnie des Indes. His brother had been implicated in the Counterrevolutionary Lyon Plot and the local population suspected that Dumontet himself had assisted in the flight to Varennes. On 26th June 1791 delegates from the municipalities of Poleymieux, Quincieux and Chausselay arrived at the château with 400 National Guard to search for arms. They were later joined by a considerable crowd. Guillin, resisted, firing potshots, the situation escalated and he was finally lynched. It was said that a local butcher dismembered his body; his head was carried to Couzon and his heart to Neuville-sur-Saône where it was eaten in an auberge. The château itself was burned down and never rebuilt. Today only a few stones and the former dovecote(the tour Rysler) remain.

"Notice sur Guillin Dumontet", in Revue des Lyonnais, vol. 3 (1836)

Camille Jordan

Camille Jordan (1771-1821) was a prominent Lyon writers and politician, who escaped to Switzerland after victory of the Convention, and later served as deputy to the Conseil des Cinq-Cents. In one of his first publications, La Loi et la religion vengées (1792) the young Jordan protested against attempts in Lyon to impose the Civil Constitution of the Clergy.

Heads of the murdered officers of the Royal-Pologne regiment are shown to the audience in the Théâtre des Célestins, 9th September 1792.

On 9th September 1792, in response to rumours of the prison massacres in Paris, eight officers of the regiment of Royal-Pologne who had been detained in the fortress of Pierre-Scize, were seized and killed, together with three refractory priests. Their severed heads were paraded around the city. In the evening, the grisly relics were presented by torchlight to terrified theatregoers in the Théâtre des Célestins.

Journée of the 13th January 1793 - the citizens of Lyon are forced to sign a petition demanding the execution of the King.

On 13th January 1793 the administration of the department met in the Hôtel de Ville to vote an address to the Convention in support of the execution of Louis XVI. In the following days many reluctant citizens of Lyon were coerced by the Jacobins of the Sections into signing a petition for the King's death.

Chalier harangues the Jacobins of Lyon

The violence of the Jacobin Sautemouche

The splendidly named Sautemouche was a officer of the Jacobin municipality, who gained a reputation for brutality. He exacted forced contributions armed with a great sabre, which he referred to as "the instrument of the law". The two demoiselles Cognet, shown in the picture, were so terrified by his depradations, that one died of fright the next day and the other lost her mind. After 29th May the rebel municipality let Sautemouche have his freedom but he was set upon by a band of muscadins in a tavern and stabbed to death.

General Kellermann

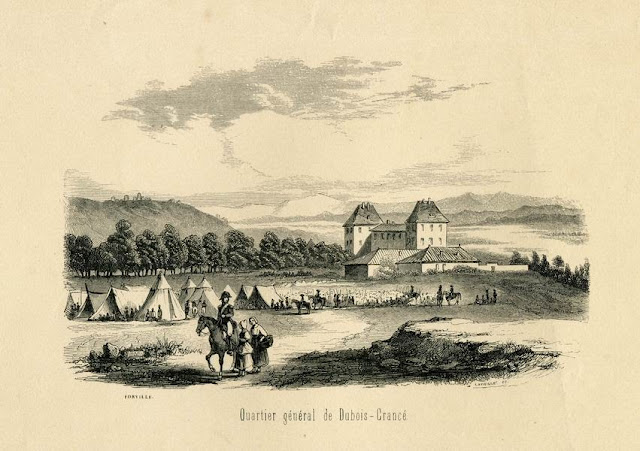

Camp of Dubois-Crancé, Representative on mission to the Army of the Alps

The courage of Madame Chappuis

This episode shows the human side of Dubois-Crancé, who was later recalled by the Convention for his lack of Revolutionary zeal. A young matron called Madame Chappuis was brought before him accused of writing a letter in which she condemned the "bloody hoards" of the Convention and wished Dubois-Crancé himself dead. So impressed was Dubois-Crancé with the courage of the muscadine lyonnaise that he let her go, commenting wrily, "We are in Sparta here, citizens!"

To be continued.