Watercolour by Moreau le Jeune, musée Lambinet

A striking image, and one which is familiar from the internet, but there seems to be no available documentation. The illustrator and engraver Jean-Michel Moreau (1741-1814) was sympathetic to the Revolution. He produced a famous engraving of the opening of the States-General in 1789 and a portrait of Charlotte Corday, also in the musée Lambinet. This is surely the archetypal "cat-like look" Robespierre.

|

| https://www.photo.rmn.fr/archive/09-518495-2C6NU097JQHU.html |

Pastel attributed to Boze, Versailles, Musée national du château et des Trianons

45cm x 36,5 cm. Sanguine, chalk and pastel on paper |

| http://collections.chateauversailles.fr/#d23f4e37-886d-49de-8f90-18767ddf60a6 |

The notice says only that the picture was the gift of M. de Knyff, in December 1952: date about 1794, "attributed to Boze"; but can all these disparate pictures really be by Boze? I suppose the experts could tell if the picture were a fake, but it looks really modern to me! M. de Knyff is probably the art historian Gilbert de Knyff.

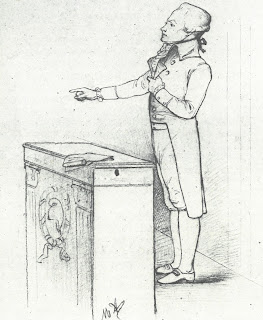

Anonymous drawing of Robespierre from the Bibliothèque Nationale

Reproduced in David Jordan, Revolutionary career, plate VI. "A contemporary sketch of Robespierre at the tribune of the Convention. The formality of his dress, including a wig, is apparent. The small, circumscribed gesture captured by the anonymous artist agress with the verbal descriptions of Robespierre's manner at the tribune. His text...is an authentic detail, since he always spoke from a text."

I can't find the drawing on Gallica.

I am just slightly worried by how close the pose is to this 19th -century engraving after Eugène Joseph Viollat (d.1901).

Portrait by the miniaturist Michel Thoüesny (1754-1815)

Thoüesny painted Robespierre's portrait in 1791 whilst he lodged in the rue Saintonge. The painting has never been identified with certainty but of interest is the revelation that Robespierre posed for it. In 1796 a certain citoyenne Naudet was interrogated and admitted to having known Robespierre: she testified "that her first husband, called Thoüesny, was a painter of miniatures and had painted Robespierre's portrait at the house of the commander of the batallion Enfans Rouge, in the rue de St.Onge (sic); that the citizen Robespierre had posed several times so that he could be painted from nature; that she believed that her husband had dined several times with the citizen Robespierre; that her husband had charged her with transporting the portrait to the rue Saint-Honoré to a carpenter's house where Robespierre then lived."

See: Michel Eude, "Robespierre et le miniaturiste Thoüesny" Annales historiques de la Révolution française (1955) 27/140 (1955), p.193-201 [on JStor]

Drawing by Vivant Denon, sold by Christie's, Paris on 23 June 2009

http://www.christies.com/lotfinder/drawings-watercolors/dominique-vivant-denon-portrait-dun-jeune-homme-de-5220320-details.aspx

Vivant Denon, claimed spuriously that this Robespierre was "by David". It seems unlikely that picture is drawn from life; but it is still worthy of note, since Vivant Denon had known Robespierre personally and was well acquainted with contemporary portraits.

These images are in Buffenoir, but not catalogued by Thompson as they are derivative.

Lithograph by Delpech

Buffenoir, vol.2(2), p. 55-6; Jordan, plate VIII, see p.254.

Buffenoir, vol.2(2), p. 55-6; Jordan, plate VIII, see p.254. Original lithograph by François Séraphin Delpech, one of a series of Revolutionary and Empire portraits produced in the 1820s. The print is best known in the version produced by Henri Grevedon. Charlotte Robespierre thought it "one of the most lifelike" images of her brother. It was probably the lithograph portrait mentioned in her death inventory in 1834.

Medallion modelled by Jacques-Auguste Collet in September 1791

Éléonore Duplay mentioned as a precious momento a plaster medallion modelled by Collet who was a designer for the Sèvres factory. Quite probably it once hung on the wall in the Duplay's salon.

The medal was subject of a 19th-century print by Léopold Flameng.

.