More from Nina Epton's splendid book Love and the French (1959) which has a particularly intriguing section entitled "Scandalous Clubs" (p.253-7)

More from Nina Epton's splendid book Love and the French (1959) which has a particularly intriguing section entitled "Scandalous Clubs" (p.253-7) This extract features information on a supposed Order of Aphrodites and is based mostly on a 1906 book by, “Jean Hervez” [aka Raoul Vèze], Les sociétés d'amour au xviiie siècle.

Here is the relevant passage:

In addition, there were secret societies whose members met to make love in special establishments devised by refined debauchees. Such where the Aphrodites, under the patronage of the Marquise de Palmazère, whose headquarters remained in Paris until the Revolution, when most of its members dispersed, either to have their frivolous heads chopped off, or to pursue their activities elsewhere.

It was not be easy to be accepted by the Aphrodites and, moreover, it was expensive. Every new member of these Order was expected to make an entrance gift compatible with his financial status, and in addition the membership fee amounted to £10,000 for a gentleman and £5,000 for a lady. Bad debtors were pursued relentlessly, but as soon as the question of striking them off the roll arose, they generally paid up on the spot to, neglecting all their other debts rather than have to relinquish the extraordinary pleasures afforded by this unique club.

|

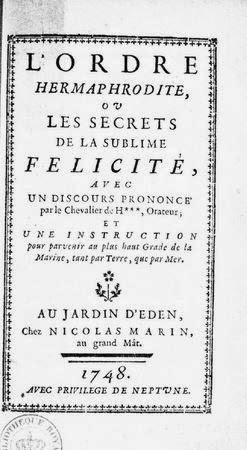

| Enjoying the Temple of Love! Frontispiece from vol. 4 of Nerciat's Les Aphrodites |

The architect of the Hospice, Monsieur du Bossage, invented a piece of furniture called an avantageuse, which was supposed to be more comfortable than the softest bed or divan and better adapted to the purpose of a rendezvous.....[For the description of this contraption, strictly in French, click here!]

Membership was limited to two hundred adepts from the aristocracy and high ranking clergy. Aspirants were thoroughly examined during a difficult amorous test that lasted for three hours, presided by incorruptible dignitaries who awarded crowns to the victors. New members who failed to win seven crowns within the three hours were not highly regarded. The admittance ceremony was a splendid affair, culminating in a fête worthy of Roman bacchanalia.

The Journal of one of the female Aphrodite has been preserved; the Lady gives the list of 4,959 amorous rendezvous for a period of twenty years—not excessive when one considers the club’s reputation. This figure includes 272 princes and prelates, 929 officers, 93 rabbis, 342 financiers, 439 monks (nearly all Cordeliers, with a sprinkling of ex-Jesuits), 420 society men, 288 commoners, 117 valets, two uncles and twelve cousins, 119 musicians, 47 Negroes, and 1,614 foreigners (during an enforced absence in London—probably during the Revolution). Like so many other debauchees, the lady had a bent for statistics

The Journal of one of the female Aphrodite has been preserved; the Lady gives the list of 4,959 amorous rendezvous for a period of twenty years—not excessive when one considers the club’s reputation. This figure includes 272 princes and prelates, 929 officers, 93 rabbis, 342 financiers, 439 monks (nearly all Cordeliers, with a sprinkling of ex-Jesuits), 420 society men, 288 commoners, 117 valets, two uncles and twelve cousins, 119 musicians, 47 Negroes, and 1,614 foreigners (during an enforced absence in London—probably during the Revolution). Like so many other debauchees, the lady had a bent for statistics

This account, with its mind-boggling furniture and staggering statistics, is to say the least improbable. Thanks to the sleuthing of Dr Patrick Spedding we now know what we suspected all along - poor Nina has been taken in! This is just a fantasy taken from a late 18th-century pornographic work, André Robert de Nerciat's Les Aphrodites ou Fragments thali-priapiques pour servir à l'histoire du plaisir (1793) - an immense rambling confection of indeterminate genre and much obscenity.

References

Nina Epton, Love and the French Cleveland: World Publishing (1959), p.256-7

André Robert de Nerciat's , Les Aphrodites ou Fragments thali-priapiques pour servir à l'histoire du plaisir 8 vols.(1793-)

/http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb33115563n

Most of the material seems to be in vol. 4.

"The English Aphrodites", posts from 2009 by Dr Patrick Spedding of Monash University Melbourne

http://patrickspedding.blogspot.co.uk/2009/08/english-aphrodites-part-1.html

http://patrickspedding.blogspot.co.uk/2009/08/english-aphrodites-part-2.html