The story continued....

The 10th August and its aftermath

p.256: On the afternoon of 10th August 1792 the Princess, together with Madame de Tourzel, accompanied the royal family as they made their escape across the Tuileries Palace gardens to the Legislative Assembly and took refuge in the reporters' box. The Princess was so ill that she was removed for a few hours to the adjacent Convent of the Feuillants and the Queen implored her not to return but to travel straight to the duc de Penthièvre at Anet. Madame de Tourzel later reported her to say that, had she not recovered, she would have attempted flight, knowing that she could be of no use to Marie-Antoinette. In the event she returned to the Loge after a couple of hours. The party was later joined by Cléry, Madame de Campan and Pauline Tourzel. Mlle Mertins, the Princess's femme-de-chambre also escaped, bringing with her all the money she could find, which the Princess then divided into three, keeping one portion herself and giving the other two to the King and Madame Élisabeth, with whom she shared a mattress for the night. The royal party spent three days in the Convent, conducted to the Assembly every morning, before finally being conveyed to imprisonment in the Temple. Some correspondence was exchanged during this time. The duc de Penthièvre apparently received letters from his daughter in-law through the intermediary of Mlle Mertins, as did Madame de Ginestous. A letter to the Princesse de Tarente, which both ladies claimed had been written from the box itself, was intercepted but proved to be merely a request for clean linen. Two guards Devin and Priquet testified to a further furtive exchange of letters - but their evidence may have been falsified to create suspicion (see Mémoires historiques iv, p.219-20; Fassy, p.84).

p.256: On the afternoon of 10th August 1792 the Princess, together with Madame de Tourzel, accompanied the royal family as they made their escape across the Tuileries Palace gardens to the Legislative Assembly and took refuge in the reporters' box. The Princess was so ill that she was removed for a few hours to the adjacent Convent of the Feuillants and the Queen implored her not to return but to travel straight to the duc de Penthièvre at Anet. Madame de Tourzel later reported her to say that, had she not recovered, she would have attempted flight, knowing that she could be of no use to Marie-Antoinette. In the event she returned to the Loge after a couple of hours. The party was later joined by Cléry, Madame de Campan and Pauline Tourzel. Mlle Mertins, the Princess's femme-de-chambre also escaped, bringing with her all the money she could find, which the Princess then divided into three, keeping one portion herself and giving the other two to the King and Madame Élisabeth, with whom she shared a mattress for the night. The royal party spent three days in the Convent, conducted to the Assembly every morning, before finally being conveyed to imprisonment in the Temple. Some correspondence was exchanged during this time. The duc de Penthièvre apparently received letters from his daughter in-law through the intermediary of Mlle Mertins, as did Madame de Ginestous. A letter to the Princesse de Tarente, which both ladies claimed had been written from the box itself, was intercepted but proved to be merely a request for clean linen. Two guards Devin and Priquet testified to a further furtive exchange of letters - but their evidence may have been falsified to create suspicion (see Mémoires historiques iv, p.219-20; Fassy, p.84).

On the evening of the 19th the order came for the arrest of the royal servants - the King's valets Hue and Chamilly, the queen's ladies, Mesdames Thibaut, Navarre and St. Brice; the Princess, Madame de Tourzel and her daughter. Marie-Thérèse later recorded a tearful parting from the Queen; according to Madame de Tourzel she commended the Princess to her care, asking her to speak for her as far as possible - maybe not just because of her weak health, but also because of the compromising knowledge she possessed.

|

| La Force Prison in 1792. Engraving from Lescure, La princesse de Lamballe (1864) |

Accounts of what happened next rely heavily on the memoirs of Madame de Tourzel. The attendants were taken to the Hôtel de Ville at around midnight in three fiacres, the princess, Madame de Tourzel and her daughter in one, the Queen's women in the other, Hue and Chamilly in the third. They were questioned one by one before Billaud Varennes in a room crowded to suffocation. Questions turned mainly on "secret correspondence" The Princess was interrogated last at three o'clock in the morning. The transcript survives, asking about secret doors in the Tuileries and furtive letters from the Temple. According to one source she had three letters, including one from the queen, concealed in her cap - making her condemnation virtually certain (Memoirs of Joseph Weber, p.481) The party was then detained until noon the following day - almost thirteen hours in all.- in the cabinet of Tallien. Since the judges were divided, Pétion and Louis-Pierre Manuel, the procureur of the Commune, were forced to report to the Assembly. In the end the women were called to the bar three times; at the second hopes were raised when they were asked if they wished to return to royal service; finally Manuel offered them only a choice between two prisons - the infamous Salpêtrière and La Force, to which they were finally driven through jeering crowds.

|

| Entrance to the Petite-Force Prison, rue Pavée (1850). Engraving. Bibl. Nat. |

|

| All that remains of La Force prison today, rue Pavée |

Madame de Tourzel, her daughter and the princesse de Lamballe were at first imprisoned separately but Manuel, softened by the charms of the Princess, soon allowed them to remain together in the Princess's room and to send for their personal effects. They were also allowed some exchange of letters and given the privilege of exercising in the open air. They spent their time in needlework and reading. Since the inmates of women's prison at La Force ("La Petite Force") were largely prostitutes, the three Court ladies found themselves assailed day and night by crude songs, jokes and remarks; ‘The least chaste ears would have been offended by everything they continuously heard, night and day.’ At one point they were mysteriously interrogated by a man who claimed to have been sent by the Princesse de Tarente, now being held at the Abbaye Prison. The gaoler Colonges attempted to compel them to sew rough linen. One biography reports the words the comment of the duc d'Orléan's mistress the Countesse de Buffon: "the ci-devant Princesse de Lamballe is without a maid and has to look after herself. For a person who affects to feel ill before a lobster in a picture this must be a rude position". By all accounts, the Princess behaved with great fortitute and, perhaps reconciled to her fate, felt in better health than she had for a long time.

Events of September 2nd-3rd

On Sunday 2nd September the young gaoler François came to report that Paris was in a state of alarm because of foreign enemies and that the women must remain confined to their cell. That evening a large unknown man came and, to her mother's consternation, spirited away Pauline de Tourzel, who was subsequently rescued by a certain Jean Hardi. On the 3rd the two remaining women were roused at six in the morning by François, who was immediately followed by six armed men who asked them their names and left. The Princess climbed up on her bed to view the crowd beneath the window. At about eleven more men came for Madame de Lamballe; Madame de Tourzel accompanied her; they were given a little bread and wine and presently ordered to descend into a crowded improvised courtroom where the Princess almost fainted. She was removed first for interrogation. For Madame de Tourzel rescue was now forthcoming. When she appearing before the tribunal, Jean Hardi and eight stout comrades crowded round her, shouted down the charges of her accusers and got her away to a waiting fiacre.

"Jean Hardi"certainly existed;see Figaro 1907/02/23 (no.8)

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k272900d/f4

Jean Hardi, cordonnier, 36 years old, electeur of the department de Paris, pour la section des Droits de l'Homme Living at 14 rue Clocheperce.

|

| Louis-Pierre Manuel by Joseph Ducreux. (Château de Versailles) |

Other accounts provide varying additional details. According to a number of the sources, the duc de Penthièvre promised the procureur Louis-Pierre Manuel half his fortune - 150,000 livres - to save the Princess and the ladies imprisoned with her. This certainly tallies with Manuel's sudden improved treatment of the women. [Though he evidently later had a genuine change of heart, since he was eventually to vote for the appel au peuple and, although retired from politics, was arrested and guillotined in November 1793].

Manuel set about the rescue, leaving the Princess strategically to last. On morning of the 2nd September, he consulted the lists and at about 10 am, he sent his agent Truchon ("le grand Nicolas") to la Petite Force where he successfully brought out Madame de Saint-Brice and Pauline de Tourzel. On the 3rd a further twenty-four women were rescued, including Mesdames Tourzel, Thibaut, Bazire, de Navarre and de Mackau. (see Fassy, p.19). But with the Princesse de Lamballe it is clear that something went terribly wrong.

Condemnation and death

The pseudo-legal improvised tribunal took place in the concierge's room in the adjoining men's prison of Grande Force; it consisted of six or seven judges, mostly emissaries of the Commune, a public accuser and a President (on this occasion Jacques Hébert). The command, "Conduct him to the Abbaye (prison)" was used as a code-word for death. The condemned were led out immediately into the yard in front of the rue des Ballets where they were bludgeoned to death. Transcripts exist of the Princess's brief interrogation: she was asked her name, position and whether she had any knowledge of royal plots on 10th August. She was then required to swear an oath to Liberty and Equality and a second to hatred of the King and Queen. With some considerable courage this latter she refused. An assistant of the court or an agent of the duc in the crowd whispered to her to take the oath and save herself. Her final words are reported: "I have nothing more to say; it is indifferent to me if I die a little earlier or later; I have made the sacrifice of my life". The judge then commanded her to be set at liberty, she was propelled out through the doors into the alley and put to death.

A last portrait

Manuel set about the rescue, leaving the Princess strategically to last. On morning of the 2nd September, he consulted the lists and at about 10 am, he sent his agent Truchon ("le grand Nicolas") to la Petite Force where he successfully brought out Madame de Saint-Brice and Pauline de Tourzel. On the 3rd a further twenty-four women were rescued, including Mesdames Tourzel, Thibaut, Bazire, de Navarre and de Mackau. (see Fassy, p.19). But with the Princesse de Lamballe it is clear that something went terribly wrong.

.According to one story agents of the duc,whether because they were anxious to find her in her cell or because they had wind of a plan to open prison doors and massacre the prisoners as they emerged, contrived to smuggled a note to the Princess insisting that she remain in her cell. When Truchon arrived, she therefore refused steadfastly to leave and the rescue attempt had to be left until she was finally forced before the Tribunal (Secret Memoirs, p.326).

Condemnation and death

|

| The Princess refuses to swear an oath of hatred of the royal family Frontispiece to Mémoires historiques de Mme la princesse de Lamballe (1801) |

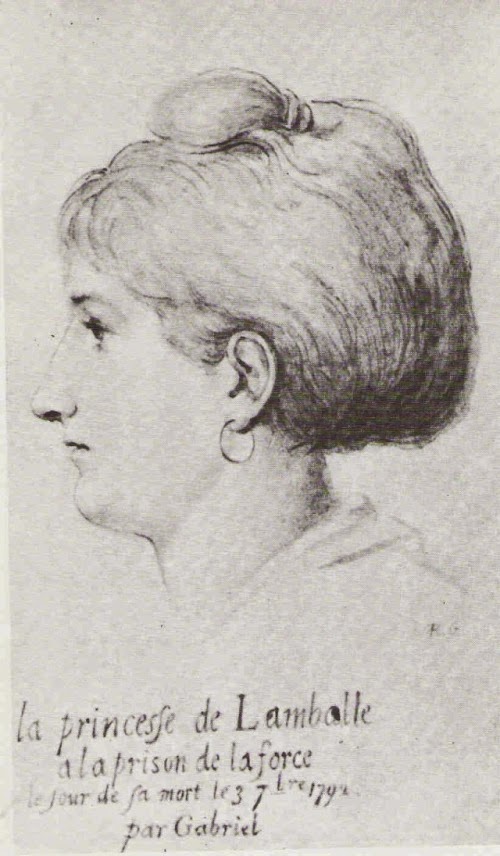

A last portrait

|

| Musée du Louvre département des Arts graphiques, 13.7 cm x 10.7 cm. |

This picture in black crayon is said to be by "R.Gabriel", drawn "from nature" immediately prior to Madame de Lamballe's assassination (see Blanc, p.205). There is no documentation for an "R. Gabriel" and the Louvre attributes the picture to the miniaturist Georges François Marie Gabriel (1775-18..) which seems correct on stylistic grounds. The version below has recently appeared on internet sites - maybe it has been sold at auction? There is also a coloured copy, signed by Gabriel, in the Versailles municipal library collection. Gabriel's claim to have been an eye-witness is, of course, pretty doubtful.

Death

Again the details are unclear. For the most part sources agree that her end was swift; emerging into the street she was struck a blow from behind which either instantly removed her skull cap or missed its mark, wounding her over the eye and causing her to stagger forward, at which point she was set upon and rapidly stabbed and bludgeoned to death. Olivier Blanc mentions a strange letter from Talleyrand to Lord Grenville (plus a memorandum by Grenville of 23 September) in which the Princess's death is described as a terrible error because "she had been taken ill and was set upon in the belief that the first blow had already been struck" (p.204-5). It is hard to know what to make of this, though it may be significant that it was Truchon, Manuel's collaborator, who held her upright as she exited into the courtyard. Maybe some eleventh-hour rescue attempt was still in the offing?

|

| Corner of rue roi-de-Sicile and rue des Ballets plate from Lenotre September massacres (1910) |

Also mentioned in the subsequent procession are Gabriel Mamin, a "famous monster" who who subsequently bragged of having ripped out the Princess's heart, and a weaver named Radi.

The Secret Memoirs somewhat curiously identifies the minster of the death blow as a mulatto whom the Princess had had baptised and educated but whom she had latterly excluded from her presence (p.327-8). There was certainly a negro present, one Guillaume Delorme (disciple of Claude Fournier) who is credited with stripping the body and wiping away the blood to reveal the aristocratic blancheur which so provocatively contrasted with his own complexion:

"a black man..and a cut-throat repeatedly sponged the bodily remains to make sure the people noticed the exquisite whteness of la Lamballe".(Antoine de Baecque, p.80)

[to be continued]

References

Besides the memoirs and biographies mentioned previously:

Besides the memoirs and biographies mentioned previously:

Paul Fassy, Episodes de l'histoire de Paris sous la Terreur: Louise de Savoie-Carignan, princesse de Lamballe et la prison de la Force (1886)

http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=wAci8goatw4C&dq=fassy+episodes&source=gbs_navlinks_s

http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=wAci8goatw4C&dq=fassy+episodes&source=gbs_navlinks_s

G Lenotre, The last days of Marie Antoinette (English version 1907)

Memoirs of the Duchesse de Tourzel (English edition, 1886, vol.2)

Antoine De Baecque, Glory and Terror: seven deaths under the French Revolution (2002)

There are also many blog and internet forum posts which cover the bases:

eg. "The death of the Princesse de Lamballe", post of 3rd September 2012. on Madame Guillotine, blog by Melanie Clegg

http://madameguillotine.org.uk/2012/09/03/the-death-of-the-princesse-de-lamballe/

Comments, with photographs and maps on the Forum de Marie-Antoinette

http://marie-antoinette.forumactif.org/t538p15-la-mort-tragique-de-la-princesse-de-lamballe

Appendix - Some thoughts on "Revolutionary" violence

Can violence ever be legitimate? In Citizens Simon Schama roundly criticises Pierre Caron' classic account Massacres de Septembre (1936) for minimising the reality of Revolutionary excess:

For Pierre Caron this kind of thing was no more than the regrettably inevitable "excesses" committed at such moments of mass hysteria. He describes the exhibition of the Lamballe head noncommittally as "the custom of those days" as though it were some picturesque folk pastime. And he goes to great lengths to dismiss stories of other atrocities as self-evident myths and items of royalist martyrology. Many of the stories - of the sexual molestation of the whores of La Salpetriere; of the mutilation of the Princesse de Lamballe; of Mme de Sombreuil being forced to drink a glass of blood in order to save her father - may have been apocryphal. But Caron's dismissal was based partly on their not being recorded in the revolutionary sources to which he gives exclusive credence; and partly on his refusal to believe that human beings, especially those claiming to act in the name of the Sovereign People, could have perpetrated anything so obscene. He was writing, however, in 1935. Ten years later, European history was again disabused of the notion that modernity somehow confers exemption from bestiality.

[Simon Schama,Citizens (1989),p.635-6].

Despite Schama's corrective, there is a similar - and disturbing - trend in recent treatments to minimise the horror of the princesse de Lamballe's death. Antoine de Baecque in Glory and Terror is interested primarily in the myths which grew up surrounding events and has this to say:

p.64-5: "The judgment and execution certainly remain unarguable, no doubt rapid, even summary. And likewise, the princess's corpse is quickly decapitated, a relatively customary practice during revolutionary massacres, inaugurated in July 1789 at the time of Joseph-Francois Foulon and his son-in-law Berthier. The head, stuck on the end of a lance, is presented to the people and to its enemies. Then the narratives begin, and make use of Lamballe's corpse as an imaginary and fantastic object."

Antoine De Baecque, Glory and Terror: seven deaths under the French Revolution (2002).p.6.

"Martyrdom of the princesse de Lamballe". This moving Youtube video was created by Jelger Bakker, uploaded 7th August 2010.

Drouot, 18 November 2020 Noblesse et Royauté Lot 7

ReplyDeletehttps://www.gazette-drouot.com/lots/13644189

Is this perhaps the original of Gabriel's portrait of the Princesse de Lamballe?