The division of the gabelle into regions, with extreme and arbitrary price differences, inevitably made the smuggling of salt an intractable problem. Smugglers were most active where the pays francs or pays rédimés shared a frontier with the grandes gabelles, above all along boundary with Brittany. Salt which sold for two or three livres-per-minot in Brittany retailed for fifty-six or more livres-per-minot over the border in Maine or Anjou.

According to Daniel Roche, everywhere in France the majority of those convicted of salt tax violations were men; two-thirds were adults under the age of forty. Smuggling was normally a supplement to other work: even the few full-time smugglers would be supported by their communities and often did ordinary chores around the villages. They were not the true marginals of society, but poor country folk - day labourers, smallholders, village artisans, petty traders. Ultimately they inhabited the same world in which the taxed salt and tobacco were consumed.

As long as individuals operated alone and on foot, the money to be made was modest - around 50% profit might be expected, but the quantities of salt involved were small - an "artisanal" level of fraud. In the towns and larger settlement, particularly along the Loire, the involvement of artisans, innkeepers and petty tradesmen encouraged some larger scale enterprise. In the 18th century professionals or semi-professional smugglers worked mainly as individuals or small groups - but occasionally there were armed troops of several dozen men, quasi -military in operation. The most dangerous operated by night, under cover of darkness. On the Breton border the landscape - with the woods and hedges of the bocages - acted in their favour, making it easy to evade pursuers and to hide the contraband. The territory round the Loire offered sizable urban outlets; Angers was only 20 km from the frontier of the gabelle.

See: Daniel Roche, France in the Enlightenment, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Harvard U.P.1998) , p.348-53.

Figures published by Necker (1784)

According to Necker, during the first three years of the Lease Salzard (1780) an annual average of 2,342 men, 896 women and 201 children were convicted of salt smuggling in the vicinity of Laval and Angers on the Brittany border. Many more women and children were arrested (or rearrested) but not prosecuted. Over a thousand horses, and fifty waggons were also seized, and 4,000 domestic raids carried out. The value of illegal salt seized and horses and wagons confiscated amounted to 280,000 livres [Quoted G.T. Matthews, The Royal General Farms (New York, 1958) p.109].

The grenier à sel at Laval

In 1974 Yves Durand and his students carried out a statistical analysis of 4,788 smugglers tried between 1759 and 1788 by the grenier à sel in Laval, a centre of the clandestine trade. These were overwhelmingly petty smugglers.

This research confirms that smuggling was entrenched in certain parishes and occupations. Of those who gave a profession, the majority were textile workers (40.8%) or agricultural labourers (31.7%). A third group (26.8%) was made up of widows, orphans, beggars or "persons without work". Over half, 2845, were women. The vast majority were illiterate - only the occasional soldier or voiturier was able to sign his name. By comparison with the previous century, fewer were armed, probably because of the threat of savage penalties. Many excused their crime on grounds of poverty. One woman said she had gone to seek salt in Brittany in order to help support her brother and sister who were confined to their beds. Others pleaded ignorance; or maintained that the salt was for herring or butter.

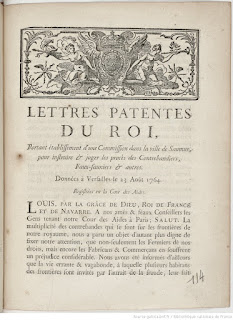

The Commission of the Cours des Aides at Saumur

The typical smuggler on the Breton border with Anjou operated "at night or very early in the morning". The salt would be taken from the areas of production to an agreed location within two leagues of the border. In 1754 a native of the Guérande was arrested in Châteaubriant with his salt loaded onto mules. His destination was a mill at Saint-Aubin-des-Châteaux about 20 kilometres from the frontier. Collection was to take place at night. The judge denounced the location as a longstanding drop-off point for smuggled salt. Other records speak of "diverse hiding places" in houses, or out in the country in the ditches, marches and woods, the majority of locations within communes adjoining the boundary with Anjou. The salt would be stored in sacks, saddle bags and cases. The smugglers would then transport it across the border and hide it again, mostly in the forest, where the buyers or a new set of intermediaries could find it. The crossing might be made either on foot or with horses. In 1763 a band of faux-sauniers was arrested at Martigné-Ferchaud with six horses carrying a total of 1400 livres of salt (that is 114 kilos per horse).

Professional smugglers were almost exclusively male. Their age range was wider than for occasional petty smugglers, who were mainly young single men. The smuggling bands included older, married men, aged up to fifty; and they sometimes had with them boys as young as fifteen. They were recruited from the poorest levels of society: casual agricultural labourers, petty artisans and traders, unemployed vagabonds. They frequently affirmed that they had taken up smuggling "pour gagner leurs vies".

Although there was still the occasional smuggler chieftain, like the famous "Catinat", even professional smugglers at this time typically operated only in small bands. Three-quarters worked in groups of only two to five. Their weapon of choice was the "frette", a vicious stick which which was capable of knocking someone out or even killing them. They sometimes carried guns or pistols, but, in this region at least, this was mainly for effect.

Alain Racineaux, 'Du faux-saunage à la chouannerie, au sud-est de la Bretagne', Mémoires de la Société d'histoire et d'archéologie de Bretagne, 56 (1989), pp. 192–206; p.198-200.

https://m.shabretagne.com/scripts/files/5f469ca2698503.09749586/1989_09.pdf

|

| Ingrandes still has the remains of its grenier à sel, prison and customs barracks. From local tourist guide: parcours-découverte.pdf (ingrandes-lefresnesurloire.fr) |

Convicts in Brest

Records of trials for petty smugglers give little information beyond name, age, profession and domicile. This study seeks to flesh out the lives of a few individuals from a range of different sources, taking as a starting point the registers of the bagne de Brest - where the majority of repeat offenders were sent in the second half of the century. 61 individuals were identified, but only ten of those appeared in more than two sources. The biographies of two are given in detail:

André Rousseau was twice incarcerated at Brest. He was first arrested in May 1764, at Ballot, fifteen kilometres outside Craon, his horse laden with salt. He was fined 200 livres, a penalty which translated into three years in the bagne. He was again arrested in May 1769, this time for smuggling salt à col, and fined 500 livres. Since he gave a false name, he was not recognised as a repeat offender until August, when he was retried and condemned to six years in the galleys. Contrary to what one might suppose, Rousseau did not come from an indigent family; his father was a prosperous weaver/merchant from the commune of Méral, and his eight siblings all had trades or were respectably married. André, the youngest, was apprenticed to a rouettier, manufacturer of spinning wheels. At the time of his father's death in April 1758, he was still a minor but presently came into his share of the property. From the judicial records in Méral, it seems André was a restless young man, who moved from lodging to lodging, entered into disputes with his the tenant of his land, and ran up debts to his brother. After his condemnation in July 1764, he was imprisoned for almost a year in Laval, awaiting the arrival of the chain-gang from Paris. During this period he was able to raise the money for the fine by selling his property to one of his brothers. But it seems he was too late, for his arrival at Brest is duly recorded in July 1765. André's condemnation was probably a source of shame to his family. He never returned to Méral and in 1769 described himself as a "journalier de profession", suggesting a more marginal status.

|

| Louis Nicolas van Blarenberghe, View of the Arsenal at Brest (1774) . A group of convicts can be seen working at the bottom right. |

Pierre Boisramé was born in 1734 and came from a family of poor weavers from the commune of Cossé-le-Vivien, about twenty kilometres from Laval. He had two much older brothers and lost his father at the age of twelve. He was apprenticed to a master weaver in the town at the age of thirteen. Like André Rousseau he seems never to have learned to read or write. He first enters the judicial records at the age twenty-four, when he was arrested as a member of a mounted band of twenty-five contrabandiers, armed with sticks and cudgels. The Commission of Saumur demonstrated its clemency on this occasion by charging him only with smuggling "avec équipage"; however, since he could not pay the 300 livres fine, he still ended up in the bagne.

When he was freed in April 1762 , Boisramé immediately returned home to claim his inheritance. He married in 1764, and over the next fourteen years, fathered 10 children. He rented a house in neighbouring Bapaume, where he paid the taille. All of which might lead one to believe he had broken with the smugglers... but this was probably not entirely the case. Records show him temporarily cultivating land belonging to neighbours, at least one of whom had been arrested as a faux-saunier. His situation therefore suggests the solidarity of smugglers and villagers in this local community.

https://journals.openedition.org/abpo/1550?file=1

No comments:

Post a Comment