|

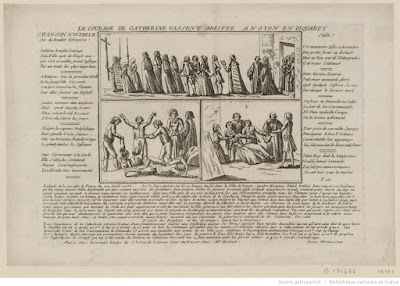

| Engraving of 1788 by Jean-François Janinet, Bibl.Nat. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8410560b/f1.item |

In 1788 the town Noyon in Picardy was the scene of a much fêted, if unglamourous act of heroism, when a servant girl called Catherine Vassent came to the rescue of four unfortunate vidangeurs, overcome by noxious fumes in a cesspit ("fosse d'aisance") Here is the story as told in the official registers of the Noyon town council:

Extract from the Register of Deliberations of the Town of Noyon, 1st April 1788

Mercure de France Sept. 1788, p.88

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=W0ddZj8n2EsC&pg=PA88#v=onepage&q&f=false

Yesterday, the 31st March, at ten o'clock in the evening, Augustin Dutilloy, Alexis Lardé, Jean Carpentier, and Pierre Leroi, all from Chiri, having undertaken to empty a cesspit in the house of Sieur Despalles, wigmaker of this town, opened up a cellar, with 14 steps down and its entrance on the street; half-an-hour later they went down to do their work. Dutilloy, going down first, fell immediately unconscious; Alexis Lardé, going to his aid, suffered the same fate. The third man, Jean Carpentier, was no more fortunate. Finally, the fourth, failing to see his comrades, went down some of the steps of the cellar; he heard their plaintive cries and went back up to Sieur Despalles to alert him to the danger. The latter gave him vinegar and urged him to go to the help of his companions. He descended with great determination into the cellar; but as he arrived at the bottom he too was suffocated by the toxic fumes.

The Sieur Despalles, taken by surprise by events, called for help. Several people gathered, including M. Sezille (the Lieutenant-General of the Baillage),M. de la Breuille (Canon of the Cathedral and Vicar-General), M. Joyant, (Commissaire of police). To begin with they threw lighted straw into the cellar but this only made the fumes more dense.

The abbé de la Breuille had vinegar brought to pour down the throats of the men and counter the effects of the poison. He proposed that someone should go down into the cellar but no one was brave enough to confront the danger. However, CATHERINE VASSENT, a servant from the neighbouring house who was present, could not resist the pull of her heart for the poor asphyxiated men, and cried out, "If I were a boy, I would go down and save them". At that moment the abbé de la Breuille, vexed by the delay, went forward himself. He washed himself with vinegar, and armed with a jug of the same, made to descend into the cellar. CATHERINE VASSENT, listening only to her courage, and guided by a principle of humanity, now gave an example of the most perfect heroism. She scarcely allowed herself a few precautions before, taking up a jug of vinegar, she herself went down into the pestilential cellar. She poured out the vinegar in different spots so that the fog dispersed and she could distinguish objects; the men, lying there motionless, came into view. She went back up the steps to get a rope; then, as soon as she had it, courageously descended again. At the bottom of the steps she saw one of the four men whom she tied by the arm; up above several people dragged him to safety, among them Sieurs Sezille and de la Breuille. The girl supported his head and managed to manoeuvre him out. She repeated the same operation for the second man, and then for the third, both of whom showed no sign of movement.

The dangers presented by that place were enough to stop the bravest man; yet a young girl of twenty did not fear to expose herself to them. Three man had already been brought out by her efforts; she was pleased to see that, thanks to the help of two surgeons who had been summoned, they were beginning to show signs of life. This reanimated her desire to save the forth, but unfortunately the fumes had affected her; after she had brought out the third man, her strength left her and she lost consciousness.

|

| Anonymous engraving of 1788, Bibl. Nat. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8410559p/f1.item |

At that moment CATHERINE VASSENT came round from her faint, gathered up her strength and courage and cried: "I won't have it said that I saved three men and left the fourth to perish for want of help." She took the same precautions, equipped herself with a hook and a rope and thew herself towards the cellar, saying, "If I am lucky I could still save the fourth!" Arriving at the bottom of the cellar and searching with her hook, she managed to find the fourth man, Alexis Lardé, who was sunk in the liquid that was all around. As soon as she touched him, she cried out miserably: "Alas he is dead; he cannot be saved". She attached a rope to his arm, held up his head and took him outside with the others.

The medical aid administered to the first three, promised that they would achieve a speedy recovery. The surgeons tried to revive the fourth but in vain. All those present could see that he could not be brought back to life; CATHERINE VASSENT was really upset; her heart was not entirely satisfied. Finally, after an hour and a half, the first three came round from their asphyxia, and the unfortunate Lardé was the sole victim.

|

Anonymous engraving, with extract from the Gazette de France, and a song

|

The making of a heroine

Catherine Vassent was an illiterate twenty-year-old servant girl who had lived all her life in Noyon and was the daughter of a humble porter. She had been very brave but she must have been quite overwhelmed by the spontaneous outpouring of official and popular adulation which her action provoked. It seems that on the eve of Revolution, popular sensibility was deterred neither by the mundane context of the deed nor the low social status of the heroine.

|

| Engraving after Gourdin, Warner Memorial Library https://www.flickr.com/photos/34039729@N04/4537466115 |

Most splendid of all, Catherine was awarded the newly established prix de vertu of the Académie française, which she came to Paris to collect in person, accompanied by two municipal officers and decorated with her couronne civique. According to the Journal de Paris, this represented a substantial 6,000 livres in silver plus a pension of 200 livres, "a fortune" says the Journal, "for a young girl of the people" - but "what fortune has every been more honourably earned or merited!"

Catherine's 19th-century biographer gives has following handy table of donations (it would seem from this that the Prix only actually yielded a more modest 1080 livres):

It should be added that the unfortunate vindangeurs were not forgotten; the duc d'Orléans produced 50 livres for the first two, 100 livres for the third who had raised the alarm and 300 livres for the wife and children of the dead man.

We know little of Catherine's subsequent life. However shortly afterwards, in the November of 1788, the son of one sieur Fargard was approved by the municipality and the duc as a suitable husband and the couple were duly married. There is one daughter in the records, born on 6th June 1790.

References

Relevant documents, reports and manuscripts are all collected together in:

René Pagel, "Catherine Vassent", Comptes rendu, Comité archéologique de Noyon.1898.

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k4537382/f103.image

A slightly variant account of events in the fosse, obviously supplied by the abbé de la Breuille, can be found in various sources, eg. Journal de Lyon, 1788, p.256

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=-_fBDWl1KiUC&pg=PA256#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Events were rapidly embellished, for instance Catherine was soon being dragged to safety by her luxuriant hair.

No comments:

Post a Comment