Now that our fatherland is welcoming its children, why must 150 thousand persons who are useful to their fellow-citizens be thus repulsed? Are we not men Frenchmen, citizens?...

Petition of 150 thousand Parisian workers and artisans, addressed to M. Bailly, secretary of the Third Estate (quoted Godechot, The taking of the Bastille, p.133-4)

Thus, on the pretext of words that I had not said, and could not have said, I was in an instant overwhelmed by misfortune.

An immense loss, a house which used to be my delight completely ruined...;but above all my good name destroyed, my name abhorred among the class of people which is dearest to my heart; here are the terrible consequences of the slander spread against me. Ah! Cruel enemies! Whoever you are, you must be well satisfied!

Exposé justicatif for Mr Réveillon, entrepreneur of the Royal Manufacture of wallpaper, Faubourg St. Antoine (written from the Bastille, April 1789)

The repression of the so-called "Réveillon riots" of April 1789 was one of the bloodiest incidents of the Revolution, perhaps leaving more dead than any rising before the journée of 10 August 1792. An older generation of left-wing historians interpreted the riots as the first stirrings of proletarian protest against the nascent capitalism represented by the Réveillon factory. Thus George Rudé in The Crowd in the French Revolution:"The Reveillon riots are unique in the history of the Revolution in that they represent an insurrectionary movement of wage-earners". (p.39) Rudé saw the trigger as dearth: "The primary cause of the disturbance, as so often in the riots of the old regime - and of the Revolution - lay in the shortage and the high price of bread" (p.44). Nowadays, the truth is recognised as more subtle. We can see in the riots both the beginnings of Revolutionary politicisation - the first realisation of the limits of popular government - , and a first understanding, however incoherent, that the unregulated labour system of nascent capitalism functioned to the disadvantage of the worker.

The context

The faubourg Saint-Antoine, where discontent centred, was home to many luxury trades that fed the capital. Although the district had one of the largest working class population, much of it outside the guild system, only about a third were wage-earners - a much lower percentage than in central Paris and the Halles district. Large concerns like the Réveillon wallpaper factory or the nearby Santerre brewery were the exception; the vast majority worked for small independent employers. These men were sans-culottes in the making. The neighbouring Saint-Marcel district was poorer, inhabited by tanners, skinners and a large transitory population of unskilled workers dependent on the Bièvre river. The harsh winter of 1788-9 saw an influx of unemployed from the surrounding countryside into both areas. This, coupled with rising food prices, was a traditional recipe for unrest. In April 1789 the Lieutenant of Police, Thiroux de Crosne, warned that "In this faubourg of Saint-Antoine we have over forty thousand workers; the high price of bread and other foodstuffs may lead to movements in the faubourg, where there have already been a few rumbles".

To be sure Réveillon's works, with its 350 workers, was a conspicuous target. Réveillon could be harsh when it suited him - he had ruthlessly evoked on the powers of the state to impose fines and break the associations of workers in his Courtalin paper mill. But in Paris there is no reason to doubt his record as a benevolent employer; his wages were fair; he was one of the few to offer some prospect of work to the excess labour force; in winter he had kept men on at his own expense, even though it had been impossible to produce wallpaper. According to Madame de la Tour du Pin he had the reputation of a kind man and was known to have rescued one of his former workers from emprisonment for debt. In fact few of the slain, wounded and condemned on record after two days of violence were actually employees of Réveillon.

In Spring 1789 the long run up to the opening of the Estates-General made for a highly charged atmosphere and a sharpened sense of grievance among the poorer inhabitants of the capital. The elections in Paris were the last to take place and the qualifications for participation were more restrictive than in the provinces; not only workers, but the vast majority of journeymen and apprentices were excluded. Those who did not have the vote were expressly forbidden to attend the meetings of the electoral assemblies. The pamphleteers protested; according to one, the disenfranchised had “nothing against them but their poverty”: “Everything is sacrificed to the owners of property, particularly the wealthy” (quoted Godechot, p.134). Although the situation remained calm, the royal government took precautions: 1,200 cavalry were stationed around the capital, the arms stored at the arsenal were transferred to the Bastille, additional security was put in place at the Invalides and the École militaire. The barrister De Lahaie remarked that the assemblies had betrayed the people's trust by hiding behind armed barriers. The drafting of the cahiers proceeded without major incident, but was a long drawn out process, and resentment was further fuelled by the exclusively bourgeois background of the 407 secondary electors chosen by the primary assemblies. One pamphet puts forward the so-called Cahiers of the Fourth Order: “Why is this immense class, made up of journeymen and wage-earners, the focus of all political revolutions, this class which has so many protests to make, the only protests which deserve, only too well, the degrading name of doléances (grievances) cast out from the bosom of the nation? Why has this order no representatives of its own?” (see p.136)

Popular fury finally ignited and centred on the hapless Réveillon , not quite by chance, but as Jacques Godechot puts it, due to “a minor but characteristic incident”. (p.136) On 23rd April Réveillon addressed the electoral assembly of the Sainte-Marguerite district which had met to draft its cahier. Despite the interdiction on their attendance, it seems there were working men present; the journalist Monjoye later maintained that "the coarsest, most ill-clad artisan" had tried to make himself heard to the contempt of the bourgeois electors. Although there is no authoritative report of Réveillon words, his theme was the revival of trade and manufacture. According to the Monjoye again, his actual proposal was the reduction of tarifs on goods entering central Paris through the Porte Saint-Antoine, a measure that would cut costs and expand production: thus he incautiously suggested that, as a consequence, wages might be lowered "we employers can proceed to a gradual reduction of our workmen's wages, which will in turn produce a gradual reduction in the price of manufactured goods" (see Godechot, p.134).

His words were soon removed from all context. He was widely reported as lamenting the days when working people could make do on fifteen sous a day - the current price of a loaf of bread. One of the rioters later testified: "he said in the assembly of the third estate at Sainte-Marguerite that workers could live on fifteen sous a day, that he employed men who earned twenty sous a day and had watches in their pockets and would soon be richer than he was." Although Réveillon vehemently denied mentioning any figure, his speech were instantly interpreted as a threat to cut wages to fifteen sous and created uproar: "Réveillon is said to have been insulted and quickly ran away, pursued by the howls of the people present, who took out their knives and started shouting, "Kill him! Kill him!" (Testimony of the china worker Olivier; see Manceron, p.441)

Similar rumours circulated concerning proposals made in the nearby Enfants-Trouvés district by Dominique Henriot, the owner of a saltpetre works.

Over the next few days tensions continued. On the evening of the 23rd, on the 24th, and yet again on the 26th, de Crosne reported an uneasy calm in Saint-Antoine. Réveillon meanwhile was elected deputy to the General Assembly of Paris which was to meet at the archbishop's palace behind Notre-Dame. Meanwhile news broke that the Estates-General which was promised for April 27th was postponed once more, to May 5th.

During the night of Sunday April 26th groups hung around Saint-Antoine and Saint-Marcel, uttering threats.

Monday 27th April

Monday was a day off in many trades. Angry and volatile crowd gathered. At about three in the afternoon a column of demonstrators left the Saint-Marcel district and made its way towards the Seine, shouting "Death to the rich! Death to the aristocrats!" and demanding bread. At their head marched a drummer and a man bearing a gibbet from which hung the cardboard effigies of Réveillon and Henriot. Others hauled about a placard inscribed with the menacing words: "Edict of the Third Estate which judges and condemns Réveillon and Henriot by name to be hanged and burned in a public place".The bookseller Hardy reported several hundred men, armed with sticks, and likewise bearing Reveillon's cardboard effigy, though in his account they were marching in the opposite direction up the rue de la Montagne-Sainte-Geneviève towards Saint-Marcel. Nearby shopkeepers had battened down their doors in alarm, but the workers, though threatening, were "doing no harm to anyone."(Hardy's journal, sheet 297, April 27 1789, quoted Manceron, p.437)] By the time the crowd fixed the makeshift gibbet in the place de Grève, it was estimated to be three thousand strong. At the nearby archbishop's palace the electors took fright; the clergy let it be known they renounced their privileges. However, three members of the Third Estate successfully harangued the crowd in the place Maubert and, in a remarkable moment of fraternal solidarity, persuaded them to lay down their batons and disperse. Shopkeepers quickly emptied the bakers' shops for fear of further disturbances. De Crosne had summoned to his office the duc du Châtelet of the French guard and the baron de Besenval, Lieutenant-General of the Swiss, but faced with contradictory reports, confined his troops to barracks and took no further action. His report to the King still spoke dismissively of the unrest as "a contemptible masquerade"

The respite was only momentary, for crowds continued to gather in the rue de Montreuil outside Titonville, where Réveillon had finally prevailed upon the duc du Châtelet to station fifty guardsmen ("We are not barbarians .....Fifty grenadiers can easily deal with men who have no other arms than their bare fists"). Frustrated, the rioters were forced to content themselves with slinging mud at the doors of the factory and with venting their fury instead on Henriot's house in the nearby rue de Cotte; he escaped to the safety of the citadel of Vincennes disguised as a servant, whilst his wife and children took refuge with friends. The property was completely ransacked, "all the furnishings, objects, linen, clothes, vehicles, carts, cabs and in general everything contained in the premises" taken to the Beauvau market-place and burned. The objective was vengeance rather than looting. According to the police report only the livestock were stolen: seven horses from the stables, the rooster, fourteen hens and fourteen ducks from the coops.

It was only at eleven on the night of the 27th, that De Crosne received news of this latest development and finally summoned troops: a batallion of gardes françaises, the Paris guard, the watch and a hundred horsemen of the Royal-Cravate regiment stationed at Charenton. He remained optimistic that the demonstration was now over.

Tuesday 28th April

On the morning of the 28th three hundred and fifty French guards mustered between the Bastille and the crossroads of the rue Montreuil close to Réveillon's mansion. They failed, however, to prevent the arrival of a considerable crowd from Saint-Marcel. Tannery workers, stevedores, the workers from the Royal glass factory in the rue de Reuilly, all swept towards the rue de Montreuil and the revolt now gained considerable momentum. Estimates put numbers at between five and ten thousand. The troups were driven back, leaving only fifty or so guards who barricaded themselves in with carts and rafters in front of the entrance to the factory and stood ready with guns primed. A prolonged standoff ensured. To complicate matters, there now arrived a number of carriages bearing aristocrats on their way to horse-racing at Vincennes, among them the duc d'Orléans who, in a typical histrionic gesture, emptied his purse in the crowd. Despite attempts to divert traffic at the barrière du Trône, the returning race-goers later again entered the faubourg. For some unaccountable reason, the duchesse d'Orléans passed along the rue de Montreuil, the flustered grenadiers were obliged to open their blockade to allow her carriage through and the crowd surged in behind, completely overwhelming the troops. They proceeded to ransack Réveillon's house, though he himself escaped safely enough with his family and household. There was little looting but a holocaust of devastation. Three enormous bonfires, fueled by paint and paper, were built in the gardens; statues, banisters, mirrors and windows were smashed, and even the trees in the grounds cut down. In two hours, between about six and eight, Titonville was completely gutted.

|

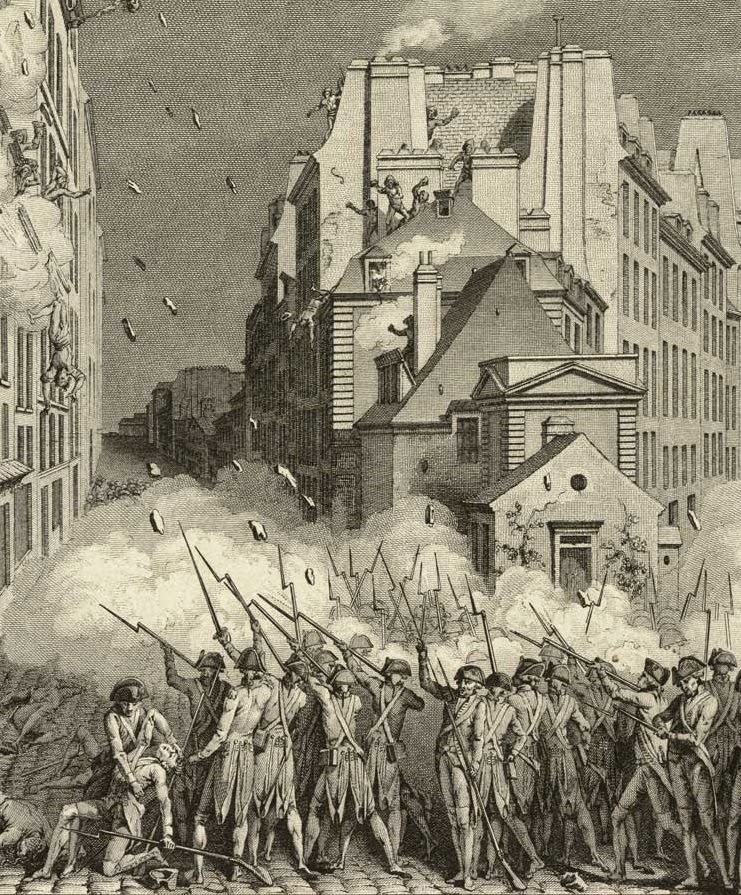

| Anonymous print, Musée Carnavalet |

.Du Crosne now took action and called up his reserve force, though it took two or three hours before the troops were finally assembled in the place de la Bastille at the top of the rue de Montreuil. Cavalry from the Royal-Cravate regiment moved in, flanked on either side by the French guard and Swiss. The rioters in their path try to give way but were prevented by the press of bodies behind. They poured into houses, pelting the soldiers from the roofs with any missiles they could lay their hands on. Shouts were heard of "Liberty" and "Long live the Third Estate! long live the King!" The infantrymen, feeling themselves threatened, opened fire, at first with blank cartridges, then finally the order was given to fire in earnest.

At eight in the evening troops forced their way into Titonville and killed most of the remaining rioters, many of whom were drunk in Réveillon's ample cellar. By nine o'clock the regiment of Royal-Cravate, at full strength, had mustered at last and scattered the remaining crowd whilst the Swiss guard, dragging their eight cannon, pursued the stragglers up to the top of the Sainte-Geneviève hill and into the faubourg Saint-Marcel.

The aftermath

Estimates of the death toll among the crowd varied wildly, from the twenty-five reported by the commissioners of the Châtelet to 900 estimated by the marquis de Sillery. A higher figure seems more likely, given that twelve soldiers were killed and eighty injured. At least 300 were reported injured. Moreover at least sixty skulls in the catacombs of Paris have been identified as likely victims (Godechot, p.147) Many were killed in the narrow congested streets off the rue de Montreuil; one eye-witness spoke of eighty corpses piled into one garden.

The reaction of the shocked and hesitant authorities was typically muted. The Châtelet, the court of summary jurisdiction for Paris, confined itself to sentencing to death two looters, one Gilbert who worked for a blanket-maker and one Pourrat, a porter on the Seine embankment. These two were hanged on the place de Grève on the 29th amid intimidating security. The King entrusted the ensuing inquiry to the Prévôt général and three weeks later seven more individuals were tried. One man, a public scrivener named Pierre Mary was condemned to death for haranging the crowd. A pregnant woman, Marie-Jean Trumeau. was reprieved, though she it was who had distributed batons and pointed out a passage that led into the wallpaper works. Five other demonstrators, workers from the faubourg Saint-Antoine, who had been found drunk in Réveillon's cellar, were condemned to the galleys for life. However, a further twenty-six prisoners had their trial adjourned, and were reprieved after the 14th July.

Having taken temporary refuge in the Bastille, Réveillon himself fled to England, though he was sufficiently patriotic not to set up in business there. The factory in Saint-Antoine, together with Réveillon’s blocks and designs, was taken on by Pierre Jacquemart and Eugène Bénard de Moussinières, who bought out Réveillon in May 1792. The firm continued in production until 1840. Réveillon later returned to France; he died in 1811 and is buried in Père Lachaise cemetery.

How did the participants profile?

Of the sixty-three addresses recorded by the Châtelet for those killed, injured or arrested, thirty-two came from Saint-Antoine and a further six from the neighbouring Saint-Marcel. The rest were from central Paris and a number from districts to the north where again factories had recently been set up outside the guild system. The workers arrested included sixteen masters or employers and fifty-two wage earners. (Godechot, p.140) According to George Rudé the men arrested - and Trumeau who was a meat vendor - could all be located in the Parisian trades. Leonard Rosenband also points out that crafts threatened by Réveillon's manufacture - printers, wallpaper printers, paperhanger, house-decorators - were heavily represented among these ringleaders (p.506-7). As Réveillon himself pointed out, workers from the factory itself were conspicuous by their absence; perhaps because they were marginalised in some way, too powerless, or simply - as seems quite likely - genuinely loyal to their employer.

Although an undercurrent of local animus against Réveillon can be discerned, in general there is little which distinguishes the crowd in the "Réveillon riots" from the more politicised participants of later Revolutionary journées. The chief difference between the bloody unravelling of unrest in April and the popular triumph of July lay rather in the response of the troops and the attitude of the Parisian authorities.

References

David Andress, The French Revolution and the people (2004), p.98-101

George Rudé, The crowd in the French Revolution (1959) p.27-44

Simon Schama, Citizens: a chronicle of the French Revolution (1989), p.326-31

Jacques Godechot, The taking of the Bastille: July 14th 1789 (English trans. 1970), p.133-51.

Leonard N. Rosenband, "Jean-Baptiste Réveillon: a man on the make in Old Regime France", French historical studies, vol.20(3) 1997, p.421-510 [JStor article]

.

Claude Manceron, Blood of the Bastille 1787-1789 [Age of the French Revolution: vol.5] English trans. 1989, p.436-47.

Translation of Réveillon's Exposé justicatif

"Exposé justicatif for Mr Réveillon, entrepreneur of the Royal Manufacture of wallpaper, Faubourg St. Antoine "in Memoirs of the Marquis de Ferrieres , 3 vols. 1: p.427-38.

https://archive.org/stream/

mmoiresdumarqui04ferrgoog#page/n453/mode/2up

"I am writing this from the sanctuary [of the Bastille], the only refuge that I can find from the furies of the multitude that rages against me. I have for consolation only the company of one or two friends, who tremble least their attentions betray me. My wife, a homeless fugitive, forced to hide the name which is dear to her, has only the sanctuary offered to her by a kindly pastor. Proscribed, objects of the most cruel and unjust hatred, neither of us know what destiny awaits us.

A further cause of pain is added to my misfortunes; my heart is torn by the plight of my three hundred and fifty workers and their families who are reduced to starvation; I hear their cries and forget for a moment my own miseries when I think of theirs. With the help of my friends I have taken what measures I can to keep the factory running.

Since for I am for the moment unoccupied, I have decided to work on my justification; when my honour is vindicated, then will be the time to recoup the remnants of my fortune.

Cruel enemies (I know not who) have painted me to the people as a barbaric man, who puts a vilely low price on the toil of the unfortunate.

I, who started out life earning my way by the work of my hands! I , who know from my own experience...how greatly the poor deserve benevolence! I who remember, and who have always taken it as an honour, that I was once a manual labourer and wage-earner; it is I who stand accused of paying labourers fifteen sous a day!

Never has slander been more unjust, and never have I felt it to be more cruel. It seems to me that a single word ought to have been enough to exonerate me.

Of the men employed in my works, the majority earn thirty, thirty-five and forty sous a day; several of them get fifty; the lowest-paid get twenty-five. How then should I be accused of setting workers’ wages at fifteen sous? But anger does not reason; slander needs only audacity.

I sense that a simple denial will not convince; enlightened men will read my words and believe me, but that class of citizen which has been prejudiced against me will not be persuaded. Only an exact and scrupulous account of my conduct in business will justify me; I shall present it to the public; I trust that I will be pardoned for including personal details….

It is exactly forty-eight years since I began, as an ordinary worker in a stationer’s shop After three years of apprenticeship I found myself, for some days, without anything to eat, any roof over my head, or almost any clothing to wear. I was in the state of despair that arises from so appalling a situation; I was perishing with suffering and starvation. A friend of mine, a carpenter’s son, came upon me; he was without money, but he sold one of his tools to buy me bread. Ah! Is a man who has know such misery, likely to forget the unfortunate so easily?

I had to get work. The sorry state I was in did not inspire confidence. The merchant to whom I was presented refused me at first, but then agreed to let me stay a few days. He saw that poverty does not always arise from bad conduct. He kept me on, grew fond of me, and I profited from his lessons.

In 1752 I was still earning only forty ecus a year; my savings when I left the merchant, amounted to eighteen francs.

Having become my own master, I preferred to work for myself. I had an inclination and natural talent for financial speculation. My first ventures did not amount to much but the success was sweet and I like to recall them. One earned me my first silver watch and another the first hundred ecus that I possessed.

That was how I started.

Shortly afterwards, my regular lifestyle and the intelligence I was presumed to possess, secured me the happiest event of my life. I obtained the heart and the hand of the woman to whom I am married; my most precious possession in prosperity and my sweetest consolation in misfortune.

It was as a result of my marriage that I started in the paper business. Economy, hard-work, exactitude – these were the first and only methods that I employed.

In 1760 they started making flocked wallpapers in Paris. I sold them at first then started manufacturing them. I had two competitors who kept their prices very high; I sold mine for half the price and, because of the care I took in their manufacture, maintained a superior quality. I had ten or twelve workers; my premises had no room for more, but demand was such I needed double that number. I then rented the vast site I occupy today. Here I employed 40, 50, 60, and finally 80 workers.

I prospered, I was respected, I was content. My workers were too; they liked me. I was happy.

But I had not anticipated the animosity and bad humour of the communautés. A succession of corporations claimed that I had invaded their rights and that one or other aspect of my manufacturing process was a usurpation. The smallest tool that I used was no longer mine, but the tool of a particular trade; the smallest design that I employed was a theft from printers, engravers, tapestry makers etc.

Magistrates and enlightened adminstrators rid me of these hindrances; I continued to perfect my products; and, assisted by the zeal and loyalty of my workmen, I came to achieve new successes.

It was at about this time that I bought the house in which I live and which since....

At that time it seemed to me a most desireable prospect. Grounds of five arpents offered me enough space for the huge works that I planned. I envisaged a community of workmen, employed and nourished by me and helping me in my work. I took pleasure in the idea and imagined that, in working for my fortune, I was providing bread for two hundred families.

In order to devote myself exclusively to this factory, the cherished object of my ambition, I sacrificed my stationery business in Paris which brought me an income of 25 to 30,000 livres. I gave this business over to two workmen who had been with me a long time and whose good conduct and intelligence impressed me; for I always valued and rewarded wisdom and merit.

However I still lacked something to complete my satisfaction.

I did not find the paper that was made then of sufficient quality for the manufacture of my wallpapers. I knew that there was a paper mill at Courtalin, near Farmoutiers, which belonged to a widow, the mother of a family, active and intelligent but without financial means. I bought the papermill. I had the good fortune to be useful to the former proprietress at the same time. She had a number of business difficulties; I took charge of them and sorted them out by patience and sound measures. I had her children travel at my expense to learn the art of papermaking. The works at Courtalin began to flourish again and became one of the best in the country. I made wove paper in imitation of the English. This successful experiment earned me the honour of the prize set up by M.Necker to "encourage the useful arts".

This price was all the more pleasing in that it was made very public at the time; also I had not applied for it, nor had anyone on my behalf.

I read with delight, and I have often reread again since, these words, engraved on the rim of the medal:

"Artis et Industriae praemium datum Joanni-Baptiste Réveillon, anno 1785".

Alas! This same medal, this prize so flattering to my work, was stolen in my disaster. In addition 500 golden louis were also taken from me. Ah! I can say from the bottom of my heart, that I would not regret the money, if I still had my medal.

Inspired by this mark of glory, I managed to take from the Dutch their paper trade as I had taken from the English their trade in wallpaper.

However, I made it my duty to give back this paper mill, in its fine state, to the estimable mother who had been its former proprietress; but I asked her for, and she agreed to, a right of inspection; I left my funds in it. I have since watched over this establishment, which is dear to me; and which was made dearer still by the idea that I was supporting there forty families of workers.

Made freer to devote myself to my works in Paris, I sought out a new means of growth.

Without having a profound knowledge of the arts, without being myself either a designer, engraver or chemist, I formed chemists, designers and engravers. I engaged them, under my direction, to apply their talents to perfect my products.

My new success excited more jealousy. A regulation appeared which was destructive to industry, and which did irreparable wrong to me in particular. The magistrates were soon disabused, they had the goodness to visit my works. The regulation was suppressed.

For my part, to put myself once and for all beyond the reach of persecution, I obtained for my establishment the title of "Royal Manufacture".

It was then that I truly tasted happiness; I enjoyed that inexpressible satisfaction felt by an honest man, who is hard working, self-made, and not insensitive to the sort of glory that accompanies useful work; who, above all, sees around him a crowd of his fellowmen, for whom he is a benefactor, whom he saves from the dangers of unemployment and who are guaranteed from penury by the fruit of their labour.

More than 300 men work every day in my workshops and receive, as I have said, a variety of salaries.

There are four classes:

The first are the draftsmen and engravers, who are more my collaborators than my employees. They earn between 50 and 100 sous a day.

The second class, made up of printers, plain-coloured sizers and coaters and carpenters, receive between 30 and 50 sous. A few, but only a very few, only earn 25 sous.

The third class consists of carriers, grinders and dressers, packers and sweeps, who earn from 25 to 30 sous.

The fourth class are children of 12 to 15 years old. I wanted their services, and in this way the could be useful to their fathers and mothers. They earn 8,10,12 and 15 sous.

Each of these classes has annual gratuities in addition, based on their salaries and awarded according to their zeal.

Finally the painters form a separate class, who are employed on a piecework rate, and can earn 6 to 9 livres a day.

Yet another type of workers are the paper-hangers; there are three foremen in this class, who are each responsible for eight to ten workers, and these earn 40 or 50 sous, and sometimes 3 livres.

A distinguished artist attached himself to my business and received annually, for his talent, 10,000 livres in fees, besides other benefits. I also employed a designer who was given 3,000 livres plus lodgings; another who had 2,000 livres and three others who each earned a fixed 1,200 livres; finally there were five clerks at 100 louis.

In short, in salaries and allowances, my annual wages bill was at least 200,000 livres.

I established among my workers the highest standards of order and discipline, without diminishing their attachment to me. Among them there were no scandals, no quarrels, no indecency, no misconduct.

As for the children, I made sure they had enough time to attend religious instruction suited to their age. I also allowed my Protestant workers to work on fete days.

Every worker was guaranteed advancement in proportion to his intelligence and keenness; and the majority grew old in my employ, knowing that I would help those loyal to me in their infirmities and give them assistance in case of need.

I believe that I have given them, this last winter, a proof of this that they will not forget. During part of the cold weather, work had to be suspended. I kept on all my workers without exception; I payed them the same wages as before; I took elaborate precautions to make sure they did not suffer from the hardships of winter.

I don't expect gratitude for this conduct; I know that the public has had the goodness to cite it as an act of benevolence; I myself regard it as a duty and would believe myself guilty if I had acted otherwise.

How could I have expected that, three months later, the people would treat me as a cruel man, insensitive to the miseries of the poor? Could I have anticipated that they would believe so avidly the lies spread about me by spiteful and vindictive enemies? That a friend, the father of his workmen, would be treated as their most barbarous enemy? That the proprietor of a works, where so many earned their subsistence, would be suddenly become the target of the hate and fury of four thousand workers?

My workers are innocent; I take no pleasure in saying it, but they know me too well; they are too honest and too attached to me! If only it had been possible for them to defend me! The house which was my delight is today a spectacle of terrible desolation. But what could they do, without arms, against a multitude which was armed, drunk and furious?

For the rest, I can say sincerely, that I don't hold anything against the people, despite the wrongs they have done me; they were carried along, but how criminal and worthy of punishment are those individuals who have led them to such excess!

One more time! I do not know, and I cannot say exactly, what mouth has blow the wind of rage into all these unfortunate people; but I know that the lies which have led them astray were hatched with malice; that they were gradually inflamed; I know that I have been depicted everywhere as a friend of the nobility, that I have been suspected of wanting the "ribbon of the order of Saint-Michel"[ie to be ennobled himself]; I know that money has been distributed to the people; I know finally that it has been said to them that I want working men to earn only FIFTEEN SOUS a day.

The result all too well fulfiled the intentions of those who spread these slanders.!

In an instant my name was given over to public execration; it was repeated with horror in the district where I live; it echoed around Paris with the most hurtful epithets; the people put me in the rank of the greatest scoundrels; they came to my house looking to tear me apart. Since I was honoured with being an elector, I was at the Archbishop's Palace; I escaped their fury; but they took vengeance on a effigy which they imagined represented me. They adorned it with the ribbon they suspected I coveted; they suspended it from a shameful trophy which they carried in triumph through part of Paris. They came immediately to devastate and burn my house; they announced their attention loudly. The presence of the guard intimidated them; they said that they would come back the next day with arms; they conferred and reappeared at midday.

It was in vain that a considerable guard was summoned to defend me. In its very presence they forced my gates, they spread out in my gardens and gave themselves over to an excess of rage that it is difficult to imagine. They lit three different fires, into which they threw my most precious personal possessions, then all my furniture, even my provisions, my linen, my coaches, the registers of my business.

When there was nothing left to burn, they threw themselves on the interior fittings of my apartments. They broke all the doors, all the woodwork, all the window frames; they reduced my mirrors to tiny pieces, or rather to dust. They removed and broke the marble fireplaces; finally, joining dishonesty to anger, they stole a large part of my silver. And as a final straw, they committed the same excesses at the home of my tenant and friend, the sieur de la Chaume.

In short, they tell me that only the sight of this destruction can give a true idea of its extent.

This orgy of rage lasted nearly two hours; then the troops, which they had had the rashness to attack, opened fire on the mob and they dispersed.

Thus, on the pretext of words that I had not said, and could not have said, I was in an instant overwhelmed by misfortune.

An immense loss to sustain(1), a house which used to be my delight completely ruined, my credit shaken, my business destroyed and perhaps without sufficient capital to continue; but above all (and it is this which overwhelms me) my good name destroyed, my name abhorred among the class of people which is dearest to my heart; here are the terrible consequences of the slander spread against me. Ah! Cruel enemies! Whoever you are, you must be satisfied!

But what have I done wrong? You have just seen; I have never done harm to anyone. I have sometimes created people who lack gratitude but I have never made people unhappy.

[(1) In a footnote Réveillon enumerates his losses:

"my gold medal; 500 golden louis; cash in silver; silverware; all the titles of my property; 7 to 8,000 livres in bills, 10-12,000 livres in designs and engravings; 15,000 francs in mirrors; 50,000 francs in furniture ; 40,000 francs in business assets - namely 30,000 in paper from my mill in Courtalin, and 10,000 in rolls of wallpaper and paints. In addition I have 50,000 to 60,000 livres of repairs and, if I wish to restore my property, I would need 50,0000 ecus".]