The suburb of Montfaucon, to the north-east of Paris, features notably in the first novel of the Nicolas Le Floch detective series by Jean-François Parot. The action takes place on 2nd February 1761 on a muddy hillside in La Villette, where two lowlife villains come to deposit a dead body. One asks if this is really where they used to hang people. His companion retorts: "They stopped hanging people here before your grandfather's time. Now there's only dead cattle from the city and beyond. It's the knacker's yard - it used to be at Javel but now it's here at Montfaucon. Can't you smell the stench? In the summer, when there's a storm brewing, you even get a whiff of it in Paris, all the way to the Tuileries!" It is a place of giant rats, where the poor come to scavenge for meat......

"Here's the knacker's yard and the tallow vats. The lime pits are further on. Walls of rotting flesh, piles and piles of it, believe me!"

Montfaucon was indeed a place of horrors.....

The Gibbet

|

| The Gibbet, recreated in 3D by Grez Productions |

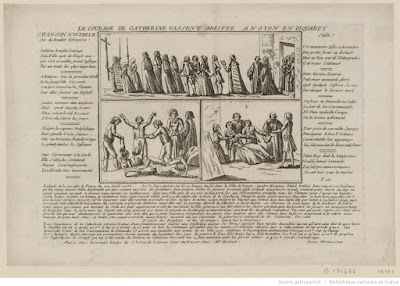

The most impressive and gothically gruesome feature of Montfaucon was the royal gibbet, which dated back to the 13th century. Strictly speaking this was a set of "Fourches patibulaires" - sandstone columns with horizontal bars from which criminals were not only hanged but their bodies displayed. Set on a natural promontory, it was a potent symbol of royal justice. By the 1620s the Gibbet had fallen into disuse; in the mid-17th century it was already described as being in a ruined state. The surrounding area was occupied by limepits (plâtrières)and served as a voirie where excrement and rubbish were collected. In 1760 - just a few months before Parot sets his tale - the whole edifice was demolished and reconstructed some 500 metres further to the north, the main motivation being to free up the existing site and move the voirie further away from the faubourg Saint-Martin. The new gibbet was a more modest affair comprising only four of the original pillars set on a square base, with a surrounding ditch and a wall. Although no-one was ever hanged there, an area at its base still served as burial place for those executed elsewhere in Paris. Thus Langilleville, 19th-century historian of the Gibbet:

When a condemned man is executed on one of the squares of Paris, after he has hanged for an hour on the gibbet, he is transported into the room at the base of the gallows; at eleven in the evening, the executioner, accompanied by his assistants, brings a cart on which the body is deposited and driven in silence, with no mark of distinction, to the barrier; there, each man lights the torch with which he is equipped; then the sombre cortege continues on its route towards the enclosure of the Fourches patibulaires, where a grave has already been dug that morning. The corpse is put in it, covered with earth, the torches are extinguished; and the next day, there is no exterior mark to indicate the whereabouts of this accursed tomb where no one comes to shed tears. (p.104-5: "note communiquée")

The gibbet was finally dismantled entirely by the Revolutionaries in 1792 when the pillars were reused to line basin in the voirie and for the knacker's chantier. There is now absolutely nothing to see apart from twin commemorative plaques.

The gibbet was finally dismantled entirely by the Revolutionaries in 1792 when the pillars were reused to line basin in the voirie and for the knacker's chantier. There is now absolutely nothing to see apart from twin commemorative plaques.

The original site is pinpointed as a set of anonymous flats in 53-55 rue de la Grange-aux-Belles which is just off the Place Colonel Fabien, home of the very modern French Communist Party HQ building. Here in 1953 construction of a garage brought to light the remains of a pillar and parts of a female skeleton. (In the Le Point video of 2014 the presenter has great fun asking bemused modern passersby the whereabouts of the gibbet.) The new position is 46 rue de Meaux, just north of the Place and close to the Marché Secrétan (an edifice of 1866, smartly refurbished in 2013)

The Sewage

The word "voirie" translates innocently enough into English as rubbish dump or refuse tip, so it took me a while to realise quite what was meant. Montfaucon was no ordinary rubbish dump, but a "voirie de matières fécales", that is a series of cesspools, which received the excrement of Paris. The products of the fosses d'aisances, the latrines and cesspits of the city, were emptied out in vast quantities by an army of vidangeurs, who transported them to Montfaucon on horse-drawn waggons or trundled them out in hand-carts. After 1781, Montfaucon became the sole voirie for the entire capital.

It is not certain when the site became administratively a voirie. In the 17th century the land belonged to Notre-Dame-de-Paris and permissions to extract limestone date back to at least 1627. In 1629 a certain Ménard asked to acquire lands at Montfaucon which he describes as a voirie "from time immemorial".(Lavillegille, p.92) In 1674 responsibility for administration of waste formally was vested in the King and became part of the charge of the newly created office of Lieutenant of Police. At this time Montfaucon was only one of several facilities, both outside and within the city walls; records from the 1720s mention others at Saint-Denis, Saint-Martin and Saint-Antoine.

The main preoccupation of the administration in the first half of the century was with improving the service of vidage. In 1727 the voiries were offered "en adjudication", that is put out to tender, for a period of eighteen years. The successful applicants were able to impose a levy of 3 sols per tombelle and were expected to maintain the voiries and the roads leading up to them. At this stage three concessions were involved: at Montfaucon, Faubourg Saint-Marceau and Faubourg Saint-Germain. In 1760 the Montfaucon voirie transferred to its new location.

In the late 1770s the design of cesspits and the system of vidage came under considerable scrutiny from the increasingly influential ranks of academic public health experts. Their intiatives were accompanied by closer regulation of vidangeurs and by the suppression of all voiries in the interior of the city. In 1781 Parisian officials closed the antiquated "voirie de l'Enfant-Jesus" in Saint-Marceau. Montaufaucon came under review, but was sanctioned as adequate for sole use, despite its proximity to to the Faubourg Saint-Martin - in the 1780s the site was a mere three hundred meters away from the new Wall of the Farmers General, within sight of Le Doux's visionary customs houses at Saint-Martin and Saint-Louis. The voirie occupied an old quarry, which provided an elevated site with different levels. In the 1780s it consisted of two settling basins at the summit where the raw effluent was directly deposited. The sediment was allowed to separate out and liquid waste (les vannes) discharged into system of lower basins and sumps. Some effort made to improve the design but the liquid effluent was still largely allowed to leech away into the soil.

|

| Voirie de Montfaucon on Piquet, Plan routier de Paris (1821) [Wikimedia Comm.] |

Eighteenth-century innovators were of course anxious to put excrement to economic use. In the earlier part of the century it had been an established privilege for the peasants and market gardeners of the suburbs to collect solid fecal matter directly from the basins as a fertiliser. The royal administration, fearful of the health hazard, tried to restrict them to material which had been in the voirie for at least three years, and forbade its use with cereal crops or vegetables intended human consumption. Sometimes necessity got the better of principle: an Ordonnance of December 1720 actually commanded the peasantry to take excess from overflowing voiries of Paris. However, perhaps through the introduction of greater regulation, by 1760 the practice of manuring the fields in this way had largely died out.

From 1785 onwards experiments were conducted to produce a more acceptable fertiliser by drying the solid deposits into a powder. In 1787 a cultivator by the name of Bridel acquired a concession at Montfaucon which he exploited until 1793 for what rapidly became the famous "poudre de Montfaucon". In this period the voirie attained truly monstrous proportions, processing 38,000 cubic meters per annum by 1791. In 1798 it was put out to tender with the expectation of a yearly profit of 64.000 francs.

|

| Plan of the Voirie in 1821 from a report by Alexandre Parent-Duchâtelet |

The Knackers' yards

|

| Views of the équarrissage at Montfaucon, from Parent-Duchâtelet's report of 1827 (fonds-ancien.equestre) |

The other nasty business at Montfaucon, again has a polite French name - équarrissage; there is no English equivalent, so we are reduced to the less decorous "knacker's yard"; it was here that horses were slaughtered and their carcasses dismembered. In a world of horse-drawn transport this was an industry of considerable proportions. No part of the carcass was wasted. Écorcheurs sold on the hides to tanneries on the banks of the nearby Bièvre River; meat, bones and horsehairs were salvaged; fires rendered the fat into tallow; even the iron horse-shoes were prised from rotting hooves.

Équarrisseurs are documented at Montfaucon by 1667, though there were many elsewhere, notably in the rue du Pont-aux-Biches, where a concentration of noxious trades offended the inhabitants of smart new houses nearby. Throughout the 18th-century ordonnances and police action attempted to force the the knackers out of town so that they became increasingly cantonised in Montfaucon. Its dominance was challenged only once, in 1780-81, when, with the backing of the Lieutenant of Police Lenoir, the chemist Cadet de Vaux briefly transferred équarrissage for the whole of Paris to a site at Javel. His experiment failed and the knackers were soon reestablished at Montfaucon.

The site is described at length by the famous 19th-century hygienist Alexandre Parent-Duchâtelet who investigated the équarrisseurs of Montfaucon in 1827. At this time there were two separate businesses operating at the furthest point of the voirie, to the north of one of the basins - you can see the basins clearly in the illustration from the report (above). The first consisted of a chantier d'équarrissage, a paved area where slaughter and initial processing took place. There were also various sheds and a tallow foundry. The second establishment was a more gruesome affair, with piled up carcasses, and workers slithering around in a courtyard covered in intestines and bloodsoaked mud. Horses arrived both dead and alive, the cadavers brought on carts, and the live animals tethered in bands of fifteen or twenty. Throughput was huge. In the 1780s it is reckoned that the knackers processed 25 horses a day, that is over 9,000 in one year.

Finally....there were the rats!

(to be continued)

References

Jean-François Parot, The Châtelet Apprentice [Nicolas Le Floch Investigations 1] Eng. trans. 2008, opening pages.

See Jean-François Parot website entry for the Monfaucon:

http://www.nicolaslefloch.fr/Lieux/Montfaucon.html

"La voirie de Montfaucon" Plateau Hassard [blog]

http://plateauhassard.blogspot.co.uk/2012/09/la-voirie-de-montfaucon.html

"Quartiers Est au 19ème siècle : ODEURS" Quartiers libres No.23, 1984

http://www.des-gens.net/Quartiers-Est-au-19eme-siecle

"La grande voirie de Monfaucon" , Quartiers libres, No.103, 2006

http://www.des-gens.net/La-grande-voirie-de-Monfaucon

Jean-Michel Poughon, "La voirie de Montfaucon, illustration d'une politique d'hygiène publique", Revue Juridique de l'Environnement, 8(3) 1983 p. 189-205

http://www.persee.fr/doc/rjenv_0397-0299_1983_num_8_3_1850

Ghislaine Bouchet, Le cheval à Paris de 1850 à 1914 (1993) p.228-30

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=oaNQ__BglQ0C&pg=PA228#v=onepage&q&f=false

I came across an old life of the Jansenist Bishop Soanen of Senez, dated 1902, which piqued my curiosity, since it was subtitled "his retraction, his death, his skull". The story of the skull appears on pg. 60, and is taken from a Lyon newspaper article of February 1890. We learn that a skull, said to be that of Soanen, had been inherited by a young man who subsequently sold it for next to nothing to an antiques dealer in the Quartier des Terreaux. He in turn sold it for 1,000 francs to a "Jansenist lady", who apparently already owned the bishop's jawbone. Sieur B. the agent who had secured the transaction, touting around the skull in a silk lined casket, now demanded 500 francs in commission and threatened legal action.

I came across an old life of the Jansenist Bishop Soanen of Senez, dated 1902, which piqued my curiosity, since it was subtitled "his retraction, his death, his skull". The story of the skull appears on pg. 60, and is taken from a Lyon newspaper article of February 1890. We learn that a skull, said to be that of Soanen, had been inherited by a young man who subsequently sold it for next to nothing to an antiques dealer in the Quartier des Terreaux. He in turn sold it for 1,000 francs to a "Jansenist lady", who apparently already owned the bishop's jawbone. Sieur B. the agent who had secured the transaction, touting around the skull in a silk lined casket, now demanded 500 francs in commission and threatened legal action.