May 2022 saw the publication of Volume 12 of the critical edition of the works of Robespierre, containing - among other items - the long awaited transcripts by Annie Geoffroy of the Le Bas manuscripts acquired by the French state in 2011. [On which see my post of 15.05.2015]

The event was marked on 8th February 1793 with a lecture by Hervé Leuwers, given at Arras as part of a series hosted by the ARBR-Les Amis de Robespierre. Here is a summary/English translation of his talk which has been made available on YouTube. As always, it is a great pleasure to rediscover that the foremost French expert on the Incorruptible is such a cheerful and unassuming scholar.

Professor Leuwers begins by reviewing briefly the background to the present publication. The work of editing the complete works was begun by the Société des Études Robespierristes as long ago as 1910. Ten volumes were eventually published, followed in 2007 by a supplementary volume edited by Florence Gauthier. Until the unexpected discovery of the Le Bas collection in 2011, it was thought that the Robespierre corpus was more or less complete.

In addition to the Le Bas manuscripts [Archives Nationales 683 AP1], the new Volume 12 contains a number of other previously unedited documents, notably papers from the financial accounts of the Collège Louis-le-Grand [Archives Nationales series H]. Also included is Robespierre's correspondence with his friend Dubois de Fosseaux, secretary of the Academy of Arras, which has been edited for the first time thanks to the work of Lionel Gallois at the Archives du Pas-de-Calais.

Professor Leuwers focuses his presentation on how the new material show Robespierre "at work" and shed light on his personality He organises the discussion around four themes:

1. Robespierre the student

The new collection includes seven documents relating to Robespierre, from the accounts of the College Louis-le-Grand, dating from 1778 to 1781.

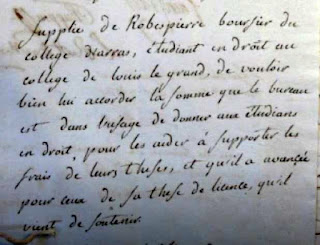

These administrative papers have not hitherto been explored. Robespierre was in receipt of a scholarship during his schooldays at Louis-le-Grand, from 1769. It is less general known that he remained a boursier throughout his subsequent legal studies and continued to receive financial support from the College. In a letter of 1781, for instance, he requests 60 livres to cover the costs of his final thesis. His handwriting at this time is clearly recognisable, though slightly more juvenile and rounded than in later life:

The texts also allow us to established a more complete chronology of the academic prizes which Robespierre won on a very regular basis. It was already known that at the end of his legal studies in 1781 he received payment of 600 livres from the College - a considerable amount of money. However, a new document reveals that he also won a prestigious general prize of the University of Paris of 96 livres for finishing first in his law class. This underlines the fact that Robespierre was an able scholar and an excellent jurist.

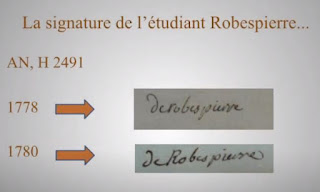

The new manuscripts allow us to compare two early examples of Robespierre's signature, one from 1778 and one from 1780.

These cast light on rival views of the young Robespierre.

The implacably hostile abbé Proyart claimed that, as a student, Robespierre had betrayed his pretensions to social status by separating the particule ("de") from the main part of his name. The new documents demonstrate for the first time that this was indeed the case. In 1778 Robespierre was still a school student, but by 1780 he was in the second year of his law studies.

Professor Leuwers cautions against over-interpretation. The use of the particule was a common variant spelling. In Robespierre's case it possibly originating with his teachers, and did not imply a claim to nobility. Although Robespierre's father wrote his name as a single word, his paternal grandmother had used the separate particule. What is certain is that after June 1790, when nobility was abolished, Robespierre the Revolutionary abandoned the particule altogether.

2. Robespierre the lawyer

The new volume contains critical editions of six "factums" or legal briefs produced by Robespierre in 1786-88 during his period as a defence lawyer in Arras.

As an up-and-coming advocat Robespierre pleaded regularly before the Council of Artois and other courts in Arras, gave consultations and published "factums" or legal briefs. Judicial memoirs of this sort, printed as brochures and distributed freely, were a commonly employed by Enlightened lawyers to sway their judges and appeal to public opinion. Robespierre is known to have written twelve, but only five had been published in the Oeuvres before the First World War. A fire in the archives of the Pas-de-Calais in 1915 then discouraged further work by destroying important contextual documents, including the entire record of Robespierre's appearances before the Council of Artois. Even in 2007, it had not been thought possible to successfully reintegrate the factums. Since then Hervé Leuwers has himself carried out research and published on them (see below). Now all but one (which is in private hands) are available to scholars in a critical edition.

Professor Leuwers emphasises that the factums are the work of a mature legal practitioner. Robespierre's new style of advocacy, imported from Paris, astonished contemporaries in Arras. In a letter of 22nd February 1782, in the archives of the Pas-de-Calais, the lawyer Ansart, writes admiringly of the 25-year-old Robespierre's "choice of expression" and the "clarity of his discourse" which was set to challenge the dominance of the local legal elite (quoted Leuwers, Robespierre (2014), p.41)Two cases from the newly published factums serve as examples. In the first, the Page case, from December 1786, Robespierre appeals against a conviction for usury. This text shows him as a progressive lawyer, advocate of radical legal reform. He attacks the competence of the judges and criticises the outmoded law which prohibits loans with interest. He also condemns the 1670 Criminal Ordinance, which, due to a series of notorious cases, was now widely seen as unduly biased against the defendant. Robespierre's rhetoric prefigures his later political speeches:

At the sight of so many scaffolds steaming with innocent blood, I learned to distrust conjectures which are given the lie by experience and nature. I hear within my own being a powerful voice, which cries out to me, always to flee this disastrous tendency to condemn on presumption....

In a note, Robespierre fears he has been too outspoken; indeed, although he won the case he was formally enjoined to expunge his criticism of judicial procedures. He was subsequently more cautious - at least until the famous Dupond case in 1789.

The second factum, on the Pepin case of 1787, is known from a single copy, rediscovered only a few years ago in the Sorbonne. Robespierre defends three well-to-do peasant farmers who contested a claim for damages from a horse-dealer whom they had injured in self-defence. This undistinguished case shows Robespierre engaged in his ordinary day-to-day legal work.

For more details, see:

https://www.cairn-int.info/article-E_AHRF_371_0055--the-factums-of-robespierre-the-lawyer.htm

3. Robespierre the politician - the new "papiers Robespierre"

The manuscripts acquired in 2011, which are edited for the new volume of Oeuvres, contains notes and drafts for a number of texts and speeches by Robespierre from 1791, and above all 1792-94.

Until 2011 these manuscripts were in the private possession of the Le Bas/Duplay family. They were consulted by certain historians in the 19th century, but had since been lost from view. Although most of the material has been previously published, the draft versions are of great interest since Robespierre always worked over his texts a great deal. Other Robespierre manuscripts are few - mostly confined to Series F7 of the Archives nationales which contains the papers confiscated at his lodgings on the day of his arrest.

Certain items have been excluded from the new volume:

AP 683/1, Item 12. Speech of 8 Thermidor [26th July 1794] This last speech of Robespierre's is already included in Volume 10 of the Oeuvres. The present manuscript, which is a two-page extract, is not in Robespierre's hand and does not represent any new material. It includes (minor) additions to the printed versions, but these had previously been indicated by Robespierre's 19th-century editor Ernest Hamel [Histoire de Robespierre Vol.3 (1865) p.720-733].

Ap 683/1, Item 2. An unpublished letter "on happiness and virtue" In this previously unknown manuscript, the author associates happiness with liberty and explains that true happiness cannot exist under a tyranny but only under a free regime. These ideas are consistent with Robespierre's, but his authorship is not proven. Detailed comparison shows conclusively that the handwriting is not his. The author also refers to his children, though this could just be a literary device. The text has already been published by Annie Geoffroy in 2013.

SPEECHES ON THE WAR

Professor Leuwers now moves on to a detailed discussion of the way in which the remaining manuscripts illuminate Robespierre's method of composition. He focuses particularly on Robespierre's contributions to the debates on war in late 1791 and 1792.

|

| Draft for speech of 26th March 1792 [Archives Nationales, AP683/1. 4.] |

The case for an offensive war was put forward by Brissot from December 1791 and opposed in a sustained fashion by several voices, including that of Robespierre. The Le Bas collection contains substantial extracts from two of his speeches, from 25th January 1792 and 26th March 1792.

AP 683/1, Item 3: Speech on the war, 25th January 1792.

Summary: Robespierre is not hostile to war; he is not a pacifist as is sometimes claimed. However, he distinguishes two types of war: the war of the despot and the war of liberty. He thinks that a war of aggression will ultimately play into the hands of the King and the executive. If it is waged successfully, the King will use it as a pretext to request the expansion of his powers. If it is lost, foreign enemies will undoubtedly move in to restore the king to his former powers. In either case the nation is the loser; the pursuit of war is a trap which will kill the Revolution, whatever the outcome. A true "war of liberty" is possible, but it requires an army dedicated to the cause and generals who can be trusted. Robespierre is wary of armed forces inherited from the Ancien Régime. He particularly fears Lafayette whom he sees as a potential new Cromwell.

AP 683/1, Item 4: Speech to the Jacobins on the present situation [Robespierre resigns himself to war] 26th March 1792

Summary: By this time the idea of a war has won many supporters. Robespierre has changed his tack; he appears less hostile to war than before. However, he is still convinced that it can be prevented. If France appears strong and determined, Austria will avoid conflict. Robespierre refers to the recent death of the Emperor as an act of Providence, a remark which roused the scorn of his opponents and created a moment of tension which marked the beginnings of the Girondin movement.

- - An initial draft: Robespierre crosses out words and phrases and replaces them as he writes.

- - A subsequent reading: He makes amendments and additions above the line of text. He also writes in the margin. Sometimes he will leave whole paragraphs and rewrite them in the margin.

- Comparison with the printed text reveals that there was also a final process of revision for publication.

- Les administrateurs

perfides/ infidèles.

- Les ennemis de la

liberté/ révolution

- Une conspiration

générale/ formidable - Les prêtres

trompoient le peuple/ secouaient les torches du fanatisme et de la discorde

References

https://youtu.be/jvco1pznFXY

https://www.etudesrobespierristes.com/2022/05/11/oeuvres-de-maximilien-robespierre-tome-xii/

https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/Robespierre

Regarding the spelling of the surname, it's worth looking at the earlier 18C family funerary monuments in St Martin's Church in Carvin. His great-grandfather is 'Martin de Robespierre'; another relative is 'Scholastique de Robespierre', while another is 'Louis Joseph Derobespierre' – so there was no consistency.

ReplyDelete