Morice was born in Paris on 21st February 1776. In 1789, at the start of the Revolution, he was working as a clerk in a notary's office. His employer later became suspect due to his aristocratic clients and counter-revolutionary opinions - he escaped death, but not imprisonment - and the young clerk, left without resources, found employment in the offices of the Committee of Public Safety. His position enabled not only to make a living but to survive the vicissitudes of the Terror. After Thermidor his office came under the Committee of Legislation presided over by Cambacérès, which dealt with many of the denunciations of former Terrorists. As head of the division of émigrés, Morice later had as his superiors Merlin de Douai and Fouché.

Morice was witness to a number of memorable events. On 10th August he was an unwilling participant in the attack on the Tuilleries; he saw the execution of Louis XVI and glimpsed Marie-Antoinette in the tumbril on her way to the scaffold. He also met both Robespierre and Carrier, as well as, at a later moment, trembling in the presence of Napoleon as First Consul.

1789: The Start of the Revolution

Morice was only thirteen years old in 1789, sixteen at the time of the Terror. Unlike the majority of his peers, he never supported the Revolution:

Whether through the principles instilled in me by my mother, whom I had recently lost, or through some other cause, I did not share the enthusiasm for the Revolution which was more or less universal among my contemporaries - an enthusiasm which was understandable when you consider how we were taught in the colleges. Our young heads were continually filled with accounts by Tacitus and others of the revolutions in Ancient Rome. Was it surprising that this generation, nourished by the milk of liberty, fell under the spell of a revolution that presented itself under the banner of liberty? Almost all my fellow pupils considered themselves to be so many Romans.

Morice's place of work was in the rue de Grenelle, not far from the rue des Saints-Pères, in a house which, by the 1890s, had long since been demolished. The notary, M. Denis de Villières, had been in practice there since 1780, and was to continue until 1822, so at this time he was still at the beginning of his career: seated in his bureau, bewigged and powdered after the fashion of the time, he would received his clients gravely. In 1789 business was much disrupted by the uncertainties of the political situation.

Morice visited the States-General at Versailles on several occasions - he was even present at the famous session in the Jeu de Paume - but he found himself only tired and bored by events. One day, however, he witnessed a scene which was still vivid in his memory years later:

I was crossing the place de Grève with my father, at the very moment when they took down the lifeless body of the unfortunate Foulon from the fatal lantern... I can still see his naked corpse, dragged along by the feet, his head bouncing on the cobbles, on its way along the quais to the Palais Royal... I can still hear the shouts of the men and woman who formed that horrible cortege... My father, who could not suppress an exclamation of horror, was almost struck over the head... He had the good fortune to escape death by losing himself in the crowd, and it was only with difficulty that I managed to rejoin him...

Supplice de Foulon a la Place de Grève, le 23 Juillet 1789, engraving after Pierre Gabriel Berthault.

https://exhibits.stanford.edu/frenchrevolution/catalog/cd267jy5088

Three months later, on 5th October, I again found myself on the square when an uncontrolled crowd forced General Lafayette to accompany them to Versailles to bring back the royal family. If the brave general ever needed a witness to the horror he felt when he was forced to concede to this mob, I would be happy to provide it....His face was as white as the linen at his neck...his appearance was a far cry from the proud show he put on when he reviewed the National Guard on the Champ de Mars.

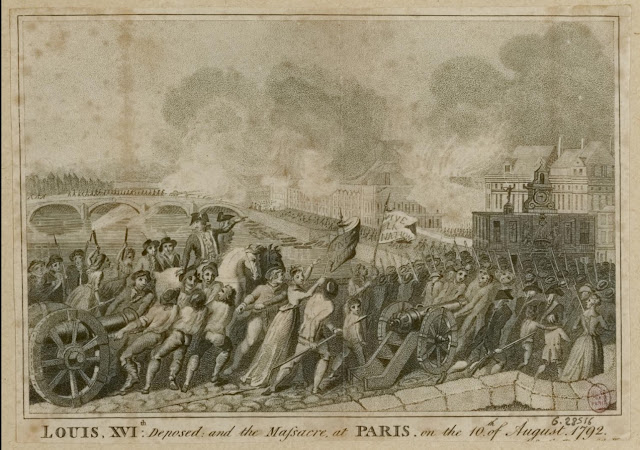

The Attack on the Tuileries, 10th August 1792.

The Revolution continued to run its seemingly inexorable course. On 10th August Morice was driven, by chance and curiosity, to enter the ransacked Tuileries palace.

For about a month, Paris had been agitated by crowds of strangers, whose tanned complexion, language and general manner revealed that they came from the South, mostly from Marseilles. Peaceful people felt a sort of anxiety, even fear, when they saw them fraternise with the vagabonds and ne'er-do-wells that had already become all too numerous in the capital. Taverns, cafés and bars were full all day and most of the night; one grew tired of the drunken singing and carousing, which in several districts obliged traders to shut their shops up early.

On 10th August 1792, bands of men began to gather at four in the morning on the place du Carrousel in front of the entrance to the Tuileries palace, where the guard had been more than doubled. The guard was composed of the Swiss, the new Royal Guard, and the National Guard battalion of the Filles de Saint-Thomas - which took no part in the action since it withdrew when the royal family took refuge in the National Assembly building.

At every moment, from different districts of Paris, new bands converged on the Carrousel. Soon the square and all its exits were blocked. The inhabitants of Paris who were not involved, became anxious. They continually went to investigate or else sent out for information. Reports varied so much from one minute to the next, that it was impossible to tell what was happening. I had already been out for news several times; at nine o'clock I decided to go again. I chanced to be on the place de la Croix-Rouge at the moment when the sans-culottes from the faubourg saint-Marceau crossed it to reach the Tuileries. They saw fit to swell their ranks with any onlookers they came across and I was swept up and forced to march with them, even though I was completely unarmed. I wasn't even wearing my hat, since I was only heading for the café at the corner of the Croix-Rouge and the rue de Grenelle, two steps away from the house of the notary for whom I worked. So it was that I was obliged to become one of the participants, or rather a spectator, of the journée.

Journée of 10 August 1792: The National Guard and the people march towards the Tuileries on the pont Neuf and pont Royal (English engraving). Musée Carnavalet

https://www.parismuseescollections.paris.fr/fr/musee-carnavalet/oeuvres/revolution-francaise-journee-du-10-aout-1792-marche-du-peuple-et-de-la#infos-principales

We came to a halt on the Pont Royal; I do not know whether this was the post assigned to my companions, or whether it was simply that they could not advance any further, but we stayed there throughout the siege, which was beginning as we arrived. I will not recount the details, which are already well known. In truth, the noise of the cannon, mixed with the shouts of those around me, and the cries of those hit by bullets from the Swiss guards entrenched in the chateau, had a terrible effect on me. It was the first time in my life that I had experienced such a situation; I saw double, or rather I saw nothing at all until the cries of victory announced that everything was over.

I decided to get out of the fray, and had already made a move to do so, when I was overcome by a curiosity natural at my age, and followed the crowd. We progressed little by little into the Carrousel and then into the main courtyard of the chateau. You can imagine the chaos of the scene. At every step your foot hit against a body or a limb detached from some body.

The courtyard of the Tuileries was not the same as it is today: it was divided into three. Where the railings are now, were the buildings where the Swiss, the Royal Guard and the detachments of National Guard were housed. These buildings had gone up in flames and when I crossed the place du Carrousel with my patrol the fire was still burning.

With difficulty I managed to enter the apartments occupied by the King and the royal family. It would be hard for me to describe exactly what was happening there. A few Swiss guards and servants who had escaped the carnage were seeking some chimney or hole to hide in. As soon as they were found, they were slaughtered, several at my very feet. Men were looting and stealing - objects that couldn't be pocketed they mutilated and destroyed. I saw broken into a thousand pieces a beautiful pendulum clock which was standing on a side table. A locksmith - or at least so I judged him to be from his dress - carefully removed the glass case and gazed on it covetously; but when he decided it couldn't be carried, he swung an enormous forge hammer and the clock, the cover and the marble console were smashed in a single blow. So close was I that I was almost injured by the pieces of metal and glass which fell all around me.

Even as they looted and destroyed, these fine gentlemen did not neglect to look for drink. The rooms where the wine and spirits were stored afforded a truly disgusting spectacle. To reach them, you had to clamber over not only over the bodies of the morning's victims, but also those of their executioners, rendered senseless by alcohol.

One of the latter, who was still on his feet, invited me to share a bottle of Liqueur des îles that he had poured into a magnificent porcelain bowl. I thought it unwise to refuse. The idea came to me to rescue the bowl but I had only gone a few paces when our hero returned and, in a stentorian voice, demanded it back. In grabbing it he lost his balance and fell; both the bowl and the flagon he held in his other hand were smashed to pieces.

Exhausted by the spectacle and overwhelmed by the unbearable heat and smell, I wanted only to leave the apartments. With some trouble I finally managed to get out.

I then made my way to the hall of the National Assembly where the occupants of the chateau had taken refuge at the first hostilities. I would never have got inside had I not chanced upon one of our clients who worked for the Assembly. He agreed to let me in provided I only stay for a moment.

The Assembly held its sessions in a large hall called the Manege, built on land which today forms part of the rue de Rivoli. It was situated to the right of the porte des Feuillants. It has since served as a Jacobin Club. Then it was made into an orangerie, and finally knocked down.

Morice now made his way out into the Tuileries gardens, where he encounter more horrors. The ground was littered with the corpses of the Swiss Guards. On the terrace opposite the rooms of Madame Elizebeth, he found thirty dead; amongst them was one of the heiduques, the Hungarian soldiers who rode behind the queen's carriage. He had been stripped of his clothing and old women exchanged cynical jokes over his body.Those who have seen Louis XVI remember his features as fine and regular but lacking in expression...When I entered the Assembly room, he seemed exactly the same as at other times I had seen him - at entertainments and public audiences; he had all the appearance of total insouciance.

The unfortunate prince was holding a large lorgnette which he raised continually, first towards the president then towards the various members of the Assembly. The Queen was very pale, but it was impossible to read her emotions. The same was true of Madame. The Dauphin behaved like any boy of his age; he seemed astonished to find himself there and could not understand why or how he had been brought. As to Madame Elisabeth, she was in floods of tears. But neither tears nor the situation of this unfortunate family could lessen the sarcasms and insults hurled by the frenzied crowd which had filled the tribunes and gathered outside the building.

I should add that during the time I was in the Assembly room, all the members who were present remained calm and behaved with decency.

Finally, Morice encountered a friend, and they left together via the passage opposite the terrasse des Feuillons. On the place du Carrousel they saw bodies piled up "like logs on a bonfire" and were obliged to wade through the pool of blood which surrounded them. At the place du Palais-Royal they made for the Pont-Neuf in order to return to the faubourg saint-Germain. On their way home, they encountered one final horror:

Near the Château d'Eau at the corner of rue Froidmanteau, lay the body of a poor Swiss guard. He had managed to escape the Tuileries, but still shared the fate of his brothers-in-arms; presumably he had been cornered at this spot and killed. The top of his skull had been separated from his head, and a dawdling woman was peacefully kicking around his brain with her foot.

A young man in National Guard uniform, who was passing by at that moment, could not contain his indignation; a crowd came to the creature's aid, and it seemed that he too was about to be murdered but, with the aid of his armed camarades, we managed to help him escape.

See: Olivier Blanc, Last letters (trans. Alan Sheridan, 1987): Emmanuel Roettiers de la Chauvinerie (1747-94), Director of the Mint during the Revolution, was guillotined with his sister on 11 Pluviôse Year II. (30 January 1794.) Blanc publishes his last brief note to his wife (p.157-9). A week before his death, Denis de Villières visited him in prison and contrived to organise the successful transfer of his property to his wife (p.78)

The following day, Morice witnessed the statue of Henri IV being toppled by the crowd on the Pont-Neuf.

The September Massacres

I was not in Paris on the 1st September. I had obtained permission to spend that day and the one following, which was a Sunday, with my father, who had a little country house in Passy. The same young man whom I had met in the Tuileries gardens on 10th August joined me. On the 2nd, after dinner, we took leave of my father and travelled back to the capital with the intention of rounding off the evening with a trip to the theatre. When we arrived at the place du théâtre des Italiens, we found the doors closed. It was the same with the Molière theatres in the rue Saint-Denis and also the theatre in the rue Culture-Sainte-Catherine. We were thus obliged to abandon our plan.

As we went along the rue Saint-Antoine to make our way home via the place de Greve and the Pont-Neuf, we noticed activity in the quarter; we even heard cries which seemed to come from the place Royale. As it was a holiday, we attributed the noise to the high spirits of the inhabitants of the faubourg and continued on our way. It was totally dark by the time we arrived at the carrefour Bussy.

I had arrived at the rue de Seine when I suddenly noticed an extraordinary glow coming from the rue Sainte-Marguerite and heard a great shouting from that direction. I approached a group of women gathered at the corner of the rue de Bourbon-le-Château and asked what the noise was about: Where can he have been? said one to her neighbour; Don't you know that business is being conducted in the prisons? Look in the gutter.

The stream in the road was red; it was running with blood. This blood came from the poor wretches who were being slaughtering at the prison de l'Abbaye. Their cries mingled with the fearsome shouts of their murderers. The glow I had seen in the rue de Seine came from the torches of the executioners and a fire of straw that they had lit to illuminate their exploits.

Although I was tired from walking, I took to my heels to flee this horrible spectacle, and got back to the rue de Grenelle pursued by the cries of the victims and their assassins.

Jean-Louis Prieur, Massacre des prisonniers de l'Abbaye, 1792. Drawing, Louvre.

https://cartelfr.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl020020541No-one was too worried about me since they knew I had been with my father since the day before. But the notary and several of my companions were terribly concerned about one of our number, who had been in charge of the guard that day and whose post was actually situated at the Abbaye prison. He had not been in contact all day and attempts to reach him had failed. We did not see him until the next day.

Our great joy at his return was some compensation to him for the horrors he had been obliged to witness. Mondon (this was the young man's name) had arrived at his guard post, where he was sergeant or corporal, when he chanced to notice among the prisoners a notary for whom he had previously worked, a M. de Mautort. At the start of the massacres, this man and several others were brought down to appear before a sort of improvised tribunal. Mondon had the presence of mind and goodness to put his police bonnet on the man's head and sling his sabre across his shoulders. Thus disguised, M. de Mautort managed to get through the entrance. Once in the the road, supported by his liberator, he was able to make good his escape.

[to be continued]

No comments:

Post a Comment